Ed. note: This is the third entry in a series looking at the three schools of philosophy for perspectives on relationships in our modern world. Inspired by Emerson’s “The American Scholar,” we are exploring timeless wisdom which endures to inform our approaches to learning, relationships and leadership. Click here for all the posts in this series.

Homer’s classic telling of Odysseus’ misfortune and adventures on his return from the Trojan War recounts a twenty year journey of testing, mythical creatures, and finally, homecoming. This epic poem is one of the earliest examples of Greek writing. In contrast to Homer’s Iliad, which is the oldest form of Western writing, Odyssey is characterized as a predecessor to the novel. In reading such a historic piece of writing, I was struck by the realization that we mysterious creatures called humans are really all very similar; we all want to be with our loved ones and are willing to endure hardships to see that through.

The first four chapters deal with the rowdy suitors who have appeared in Odysseus’ absence and their appetites, which threaten to drive Odysseus’ wife and son from their home. Hospitality is famously a source of pride for the Greeks, and is a theme throughout the poem. The suitors courting Penelope and feasting regularly at the household’s expense serve as examples of hospitality run amok.

Having received the goddess Athena’s encouragement, Telemachus determines to set things right in his house and embarks to find more information regarding his father’s fate. Athena personally makes arrangements for Telemachus and intervenes on his behalf several times throughout the poem.

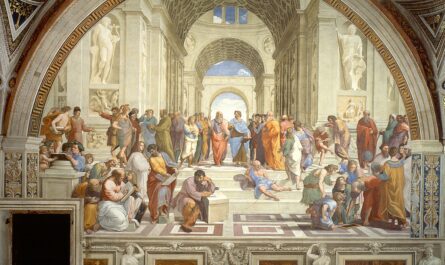

In the fifth chapter, the narrative shifts to Athena expressing distaste for Calypso and her captivity of Odysseus. It is here that we pick up with Odysseus’ journey and hear about his encounters before being held by the love-struck Calypso. The subsequent chapters weave princesses, kings, Cyclops, and cannibals into our hero’s journey. We are introduced to a cast of gods who are enraged, kind, loving, and conniving in turn. The gods are portrayed here in a less grand manner than one would perhaps expect as they interact directly with Odysseus and Telemachus several times.

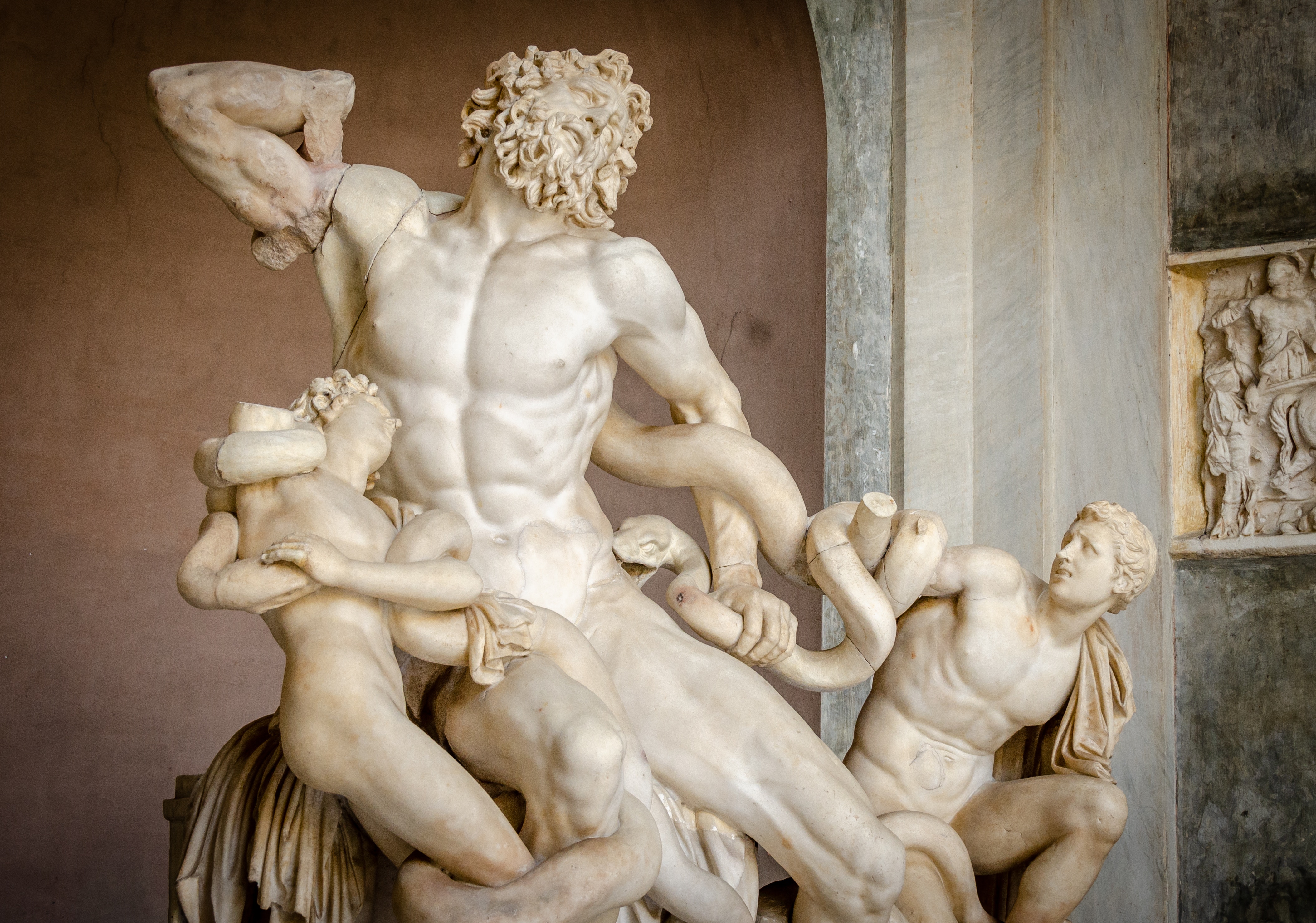

In an encounter with the souls of Hades (including a mention of Oedipus), Odysseus speaks with Teiresias; his mother; King Agamemnon, whom he killed in battle, and Achilles.

The second half of the poem details Odysseus’ eventual return to his homeland of Ithaca, and a final confrontation with the rowdy suitors who opened the story. The climax, hinging on the mistreatment of a beggar, the disguised Odysseus, seals the fates of the unwelcome suitors and reinforces the priority of hospitality of the Greeks.

The topic and characterizations of women throughout the Odyssey are complex and interesting. While some females are cast as seductresses, the prime motivator for Telemachus – and to whom Odysseus can thank for putting his return in motion – was Athena, a powerful goddess of strategic warfare and the half-sister of Ares. Queen Penelope is also clever in dealing with the gathering of unwanted suitors; she undoes her bridal weaving each night, putting off the raucous men and also seducing them into giving her gifts, all along clearly having her heart set on Odysseus’ return. The goddess Circe is a witch who was depicted as ruthless in her first outing and later redeems herself. Calypso also shows several dimensions; she is in love with Odysseus, but obeys the will of the gods and is convinced to make arrangements for his travel back to Ithaca.

The men, Odysseus and Telemachus, are strong, holding themselves nobly, yet they also demonstrate their love for family. Odysseus, as a king and warrior, shows compassion for his men as they find themselves on this serpentine journey.

Because of its age and expanse, this story has influenced literature for centuries. The most frequently cited contemporary examples are the Marvel comics adaptations, Ulysses by James Joyce, Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad and the Coen brothers’ film O Brother, Where Art Thou? The story still speaks centuries later because it highlights values which are human and universal; perseverance, the fear of unknown consequences and beautiful love and longing for home and family.