The past six months living here in the German countryside has brought home several lessons about this historic place, as well as myself. Despite the beautiful surroundings, the first few months threw a few curve-balls; not because of any particular failing, but simply due to the unfamiliarity of living in a new country. Moving overseas combines all the stress of international travel and language barriers with house hunting, learning new routines, and unpacking your entire life – barrels of fun, right? Upon arriving in any new place, it’s easy to be bombarded by the number of things you simply don’t know. This was certainly true in my case. The language, for starters, but even small details like front doors locking automatically, card readers having different setups than in the States, recycling being separated differently (and more rigorously, which is great); all combined to present a nearly inscrutable exterior and made for a few surprising afternoons. There have been many more pleasant experiences than embarrassments, though.

Thinking back over my short time here, three ideas stand out. My first takeaway is learning to be patient and to structure learning in intervals. I was quickly overwhelmed by trying to learn too much at once and ended several days frustrated. Then I adopted a proactive approach; instead of being overwhelmed by the huge number of tasks to complete and unfamiliar things to learn, I drastically reduced the number of things to focus on, “requiring” myself to only complete two things each day. By setting aside specific times for work and language lessons, I gave myself permission to do nothing else if I felt like it. I gave myself more time not spent specifically working toward any sort of goal, because frankly, every aspect of the first few months was work. On days I was feeling more ambitious, I did more, and if I didn’t feel ambitious, I had still accomplished a few things for the day. Learning to be patient and trust the compounding process made the difference in my first few months here. You have time. You can only study so much each day, and you’ll pick up the conversational exchanges faster than you think.

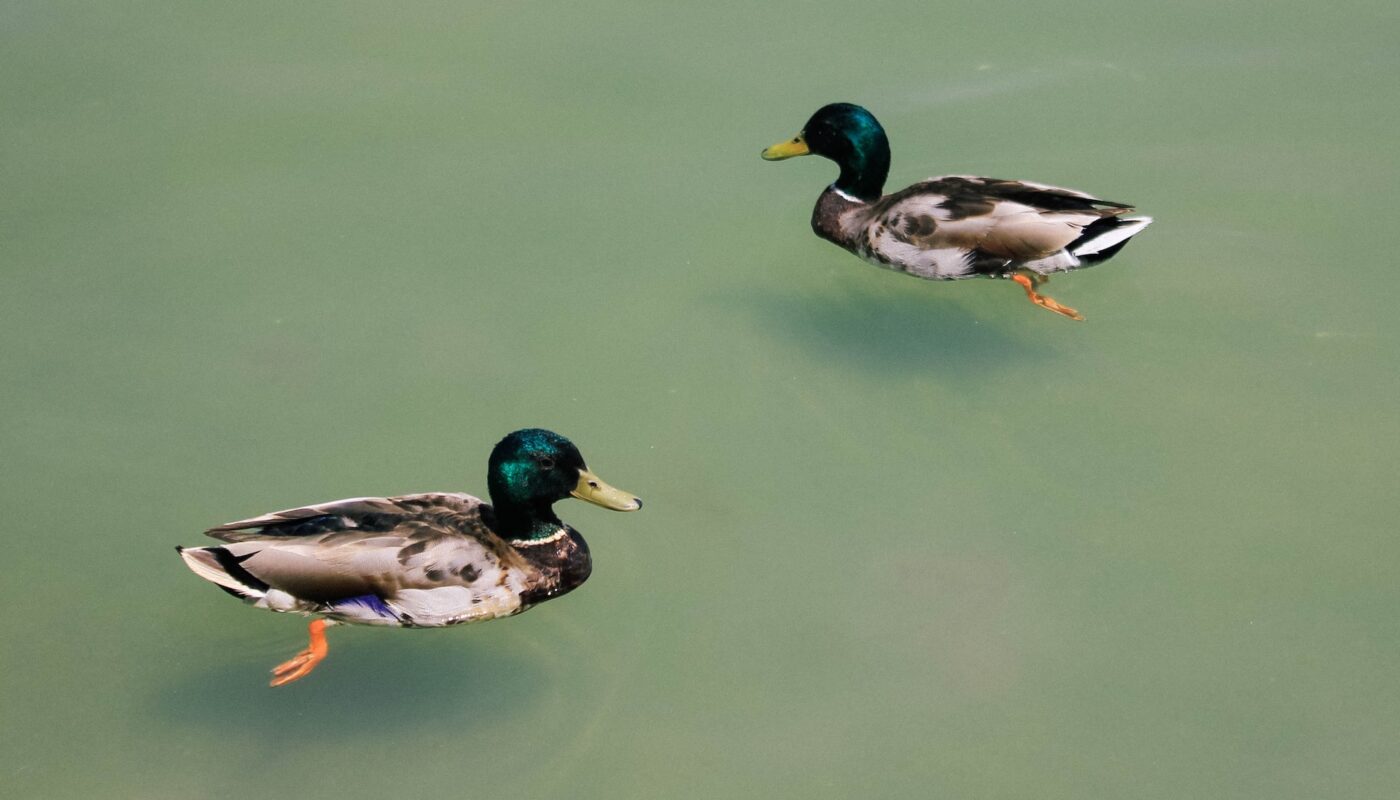

My second takeaway is to get regular exercise and follow the locals’ lead in doing so. The first thing I set out to find upon moving into our house was a walking path I could frequent on daily walks or runs. This particular one took me from the house to the local bakery. Exercise, as anyone who knows me at all knows I consider a firm priority, helps in keeping stress levels manageable and clearing the mind. Shortly after that, I happened upon a running path leading from the middle of town to its outer edge, lined with trees, smoothly paved, and populated with runners and walkers. Shortly thereafter, we discovered a park in the middle of town, with a large pond, inhabited by ducks [1] and other fauna. Exploring the town, getting into a weekly routine, and being out with others enjoying the fresh air went a long way in helping me learn and adjust to the town’s rhythms.

Thirdly, don’t fear looking foolish. My mantra for the first few weeks was, “I will never know less than I do right now,” and with that I jumped into learning the language, shopping in boutiques all around town, dining in restaurants, and just accumulating knowledge about this town and nation and how things are done over here. The idea was banishing the “first time” jitters from as many things as possible. Did I have a few cringe inducing moments? Of course! I have learned so much since those first few weeks, though, they no longer really make an impression. At some point, you just have to start speaking, start exploring, and see how things go.

Above all, through my observations and adjustments to life here, I have seen firsthand how seriously the Europeans take leisure. This becomes even more significant when you look at how Europeans approach every day life versus Americans. The regulations around everyday life, including food and the environment are pro-active, not reactive, which requires manufacturers to prove their methods and products will not cause harm before approval. The country shuts down on Sundays, guaranteeing a full day of rest for all workers, a protection we still haven’t secured in the States. Like Sundays, holidays are also “Quiet Days,” which means no one should be making noise to disturb their neighbors; no noisy lawn equipment, no loud music, and no hammering on walls you share with a neighbor. The Germans take this particularly seriously; one Sunday I was picking weeds from our flower beds and a neighbor called out that Sundays were for no work at all, only relaxing. I responded that I considered getting rid of weeds relaxing and he just laughed. It did stick with me, though, that even the simple pulling of stray grasses could be considered work.

The German philosopher Josef Pieper wrote [2], “There is no need to waste words showing that not everything is useless which cannot be brought under the definition of the useful. And it is by no means unimportant for a nation and for the realization of the “common good” , that a place should be made for activity which is not “useful work” in the sense of being utilitarian.” Reflection upon one’s recent journey, contemplation of the divine, rumination over the qualities and ideals one wants to embody; these are hardly utilitarian concepts, but they are required in the thoughtful life.

Footnotes:

1) One of which was with her new brood of ducklings who followed her as she walked along the pathway next to my husband and me. Yes, sometimes living in Germany really does feel like living in a fairy tale.

2) Leisure, the Basis of Culture, Josef Pieper. (1963, English translation)