Ted Gioia asks, “Are we in a crisis of seriousness?”. The answer is a resounding, “Yes!”. More specifically, converging crises have produced a tendency in American society toward the unserious. While a serious person is able to focus their attention on the things they consider most important, many aspects of our modern society make this attention and concentration difficult to maintain.

Social media, smartphones, and “Breaking News” have had a cumulatively negative impact by decimating attention spans. The concepts of attention hijacking and “gambling mechanics” used by tech companies profiting from “surveillance capitalism” are well established by the work of writers like Cal Newport and Johan Hari and social psychologist Jonathan Haidt. To summarize, technology companies track your activity online, compile a “file” of sorts, then serve you advertisements, often conspicuously places, which are targeted to appeal to you based on that file. The smartphone’s notification signals combined with the introduction in 2012 of social media “like” or “repost” buttons unleashed a wave of instant dopamine sources, over time prompting hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of users into compulsively checking their phones every few minutes for updates. Over time our attention in the online world has been decimated, as frequent social media users have become more and more accustomed to the immediacy of social media interactions and constant dopamine hits in the form of updates, feedback, and social validation on their posts. Even outside of social media, online ads make it all but impossible to read a page without something blinking or popping up to offer you something.

This fracturing of attention has not been limited to social media platforms. Another egregious form of fracturing attention can be seen in the “Breaking News” updates now employed by many news outlets. Whereas journalism by its very definition requires time, sustained attention, and thought to responsibly produce, “breaking news” alerts are the antithesis of all these things. It takes time to gather facts, to consult with experts, and to form an informed opinion on any topic worth committing to paper. “Breaking News” posts even contain a disclaimer that “details may change” as the reporters and journalists gather facts and analysis. In other words, “the initial picture will be different as reporters and journalists actually do their jobs, but we, news outlets, are so desperate for the advertising clicks and page views, we will put up unverified information and change it as we can establish facts”. The result has been around-the clock-reports of events, updated every few minutes on a web page, which again plays into this ‘dopamine hit’ culture and the further fracturing of attention. In most of today’s Internet landscape, we have less inclination and fewer opportunities to hold our focus on difficult and serious topics and further our attention spans.

The ability to concentrate on one thing is becoming increasingly rare, as even passive entertainment becomes background entertainment. Thanks to a widely quoted report by Will Tavlin, we now know Netflix has directed their studios to make their series and movies more suitable for “background entertainment” as people increasingly attend to multiple screens in their entertainment hours. Tavlin writes, “Several screenwriters who’ve worked for the streamer told me a common note from company executives is ‘have this character announce what they’re doing so that viewers who have this program on in the background can follow along.’” While it has been common for Americans to come home and watch a few hours of evening television each night, we have entered a strange state of affairs, where multiple devices are engaged to keep our minds amused. The combination of “mindless scrolling” (an action done without thinking, for the purpose of being vaguely amused) and background shows holds just enough of our attention without requiring any sustained thought. Vegging out on one screen is no longer enough!

Americans spend a majority of their free time on passive entertainment. The days of analog hobbies keeping us moderately active, like fishing, woodworking, gardening, are mostly gone. Instead the average American spends six hours daily watching video, and averages just over two hours per day on social media. (We don’t yet have data on how much of that overlaps.) In contrast to hours spent on entertainment, the average American day includes very little movement, taking the car from home garage to parking garage, the elevator to the correct floor, and sitting in an office chair for eight hours. Then, the drive back home, often while listening to a podcast or audiobook, to sit in front of the television and scroll on our phones. Rates of U.S. adults hitting the low 150 minutes of activity per week recommended by the Centers for Disease Control are dismal, at only twenty-eight percent. American reading rates continue to remain low. One journal found American diets to be around sixty percent processed food, the highest rate on the planet. (Though it should be noted the category “processed foods” does include frozen meals and vegetables.) It’s safe to say we don’t take moving seriously. A person who does not eat vegetables does not take health seriously. A person who does not read does not take thinking seriously.

Even more troubling, we have mistaken access to information for possessing knowledge. Our ability to look things up instantly has eroded the value of knowing things. The decline of expertise, for several reasons, has left a void in the culture as to what can be stated as fact. There has been no shortage of people looking to capitalize on this fact. Our inability to sit with uncertainty or incomplete data has led to simplistic explanations masquerading as answers to complex topics, robbing ourselves in the process of the opportunity to develop deep understanding of a topic and inflating our hubris at the same time. This leads us to think we “know all about” something because we spent an evening on the Internet watching videos of other people talking about the topic. Further, an insistence to quash debate on hot-button topics in preference for one “final word” suppresses the very concept of working to uncover what is true. Overall, the numbers paint a rather bleak picture of a society concerned with the tasty, the easy, and the immediate, prone to ignore the consequential and important. In other words, an unserious society.

Defining Serious

What exactly does ‘serious’ mean? Merriam-Webster defines ‘serious’ as “thoughtful or subdued in appearance or manner”, or “requiring much thought or work”. The Encyclopedia Britannica offers, “involving or deserving a lot of thought, attention, or work; or giving a lot of attention or energy into something”. Lastly, the Cambridge dictionary includes this interesting variation; “needing or deserving your complete attention”. To be serious, then, means to think deeply and attentively.

Dorothy Sayers addressed the concept of thought and its decline in our society in her speech, “The Lost Tools of Learning”, delivered all the way back in 1947. She asked two questions which I will pose to the reader; the first,

“Have you ever, in listening to a debate among adult and presumably responsible people, been fretted by the extraordinary inability of the average debater to speak to the question, or to meet and refute the arguments of speakers on the other side?”

The second,

“Are you occasionally perturbed by the things written by adult men and women for adult men and women to read?”

Today, commentators commonly attribute the decline in thought and seriousness we see to the influence of postmodern thinkers of the 1950s and 60s, but we can see from Sayers’ “Lost Tools” that this decline predates those postmodern thinkers. Standards of thought and public discourse were observably declining as early as the 1940s.

Sayers argues these standards of thinking and discourse declined because education objectives changed from teaching students how to learn to instead teaching students facts about subjects, omitting the foundational structure of learning. To think well and diligently requires sustained concentration on a topic, developing a deep understanding of it, and thoughtfully presenting your thoughts and conclusions on it. The majority of students in Sayers’ time were not taught how to learn because they were not taught how to think well and diligently – and this continues to be the case. As a result, we find ourselves in a society largely lacking in the ability to think well. This is now being exacerbated by devices and practices which actively erode our ability to sustain concentration. As we’ve seen, time and attention are in short supply.

The difference between a serious person and an unserious person comes down to intention and attention. How much intention does one lead their life with, and how do they attend to their attention? A serious person has spent time considering what they want to do and the best way they can go about doing it. Then they set about doing it, taking necessary steps to protect their time and attention.

One of the most vivid examples of the contrast between a serious person and unserious people is found in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. The story follows Fannie Price, the daughter of a woman who married a less-than-reputable man and had more children than they could afford to feed in Regency England. In an effort to help ease the family’s economic woes, sixteen-year-old Fannie goes to live with her wealthy uncle. She learns and observes the social norms of the time. She receives an education. She is expected to converse with and entertain her aunts. Her wealthy cousins, while well-dressed, moving in the proper social circles, and boasting the highest educational opportunities, prove themselves over the course of the story to be poor in thought and poor in character.

Fannie spends much of the story deep in thought, weighing the choices she’s seen her cousins make against what they’ve all been taught. She struggles finding herself the object of unwanted attention and finds her character called into question. The cousins end up making terrible decisions in life and love because of their inability to be serious, while Fanny, despite hailing from a humbler background and less extensive education, ends up the heroine, making prudent decisions after much consideration. Fannie is able to recognize the flightiness and lack of seriousness of the Crawford family because she understands and practices the basic expectations of honesty and loyalty. Fannie takes the time to consider which choice is right, rather than simply choosing what is immediately inviting, and this ability to think, the ability to be serious, ultimately wins the day.

More than once while reading Mansfield Park, I had an internal debate as to whether Fannie was holding herself to high standards or if she was simply being judgmental. How often today are the two considered one and the same?

Austen’s point is that character and good decision are not guaranteed by being born poor nor rich. Thinking well and thoroughly is the result of years of instruction and molding, a blend of nature and nurture in response to a person’s natural inclinations. Most importantly, thinking requires time and attention to do successfully.

If today’s algorithm based, attention-hijacking tech is the problem, then the answer is to practice holding our attention on what makes us human and what has made us human for centuries. Fortunately, we live in a time of abundance, with a wealth of history, literature, and distilled thinking available at our fingertips. We just have to sift through it. The mark of a serious person is to direct their attention and sustained thought to those topics deserving of it. To answer Gioia’s question, yes, there is a crisis of seriousness, but it is one we can still repair, granted enough of us put our minds and tools to use.

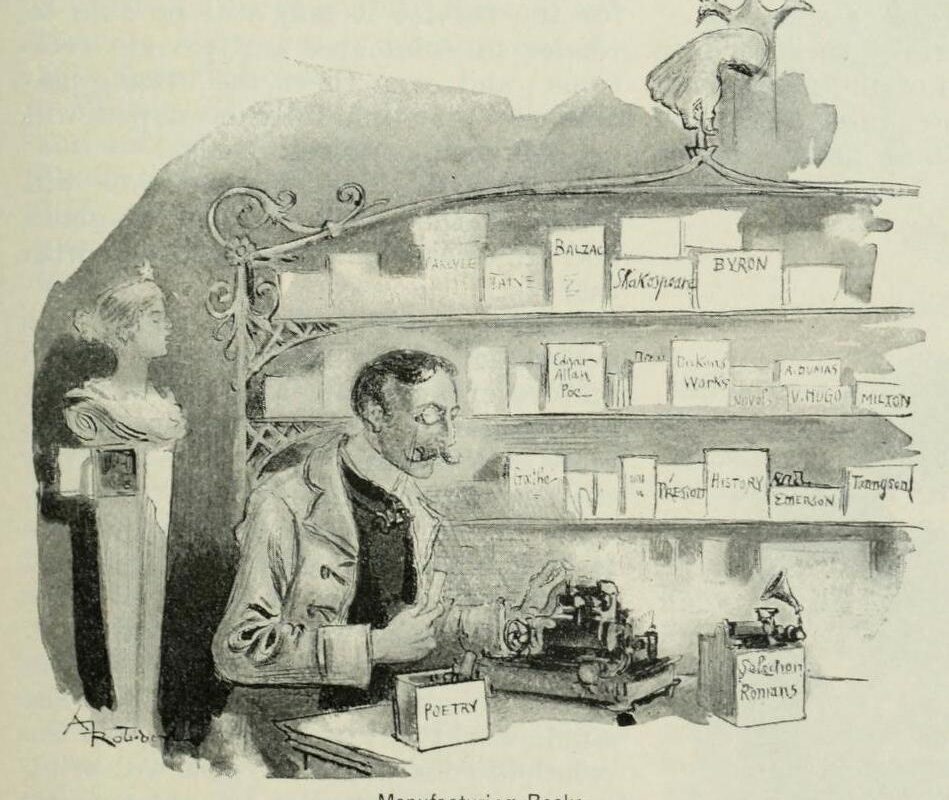

Image: The End of Books, Robida, Albert. Scribner’s Magazine. 1894.