We should “attend to our freedom wisely,” as the philosopher says. Our always-on devices provide a superb means of passing time. They often carry us from one task to the next, and can make work and communicating nearly effortless. In recent months, I have (re)discovered via a weekly break from digital tech, that a day without constant wireless connection feels like a wide expanse of time. I’ve encountered less distraction, fewer instances of time “flying,” and more intention and concentration.

It is not about “anti-tech”

Whether it’s playing games or streaming videos, dozens of hours each week are spent online. Yes, we can scroll hours away on social media apps, of course, but these platforms are far from the only places time disappears. It might be responding to others on forums, idling away hours streaming shows, scouring news websites for updates or camping out in comments sections; the Internet’s avenues for losing time are unmatched.

At the same time, our devices and our technology also enable much good. Many of today’s advances in medicine and in access to education wouldn’t otherwise be possible. It also enables communications otherwise hampered – I can speak with my family on the other side of the globe because of advances in wireless technology. Technology enables and simplifies many things which were difficult or impossible just a few years ago. However, if we aren’t watchful, this same technology can also rob us of time.

Taking a regular break from technology is not about being “anti-tech”. It is not even about technology, primarily. Too much of anything tends to have negative consequences. As finite beings, one of our chief concerns should be using our time mindfully and with purpose. The focus is on being a human and setting aside time specifically to be more human.

Time is elusive

“What we plead against is man’s unconditional surrender to space, his enslavement to things. We must not forget that it is not a thing that lends significance to a moment; it is the moment that lends significance to things.” – Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Sabbath

In his 20th-century classic, The Sabbath, Rabbi Abraham Heschel describes the day of rest as an opportunity to reclaim how we think about and experience time. He describes the Sabbath – the seventh day of creation set aside for rest – as a “sanctuary in time”. I find this a particularly valuable mindset, especially on the weekends. The term ‘sanctuary’ describes a sacred place, one set aside for a special purpose. The term is often used to describe a church, temple, or mosque, but can more widely refer to any place of safety. Therefore, this day of rest, as Heschel uses the term, is meant to be a “special place in time”. “The meaning of the Sabbath,” Heschel writes, “is to celebrate time rather than space.” I initially picked up The Sabbath because I was interested in the Jewish tradition of thinking on the topic of time. What I discovered were, among other things, perceptive observations about a different way of being. That is, an outlook concerned with Time and not with Things.

Heschel goes to great lengths to sketch the ways in which Judaism is concerned with time and with attending to time well, rather than being distracted by objects. He talks about maintaining the ability to not be possessed by things, a constant struggle. Those of us with too many things may find ourselves trapped by taking care of them, while those who don’t have enough are preoccupied with gathering more. It’s a rare quality, indeed, to be more concerned with time and using it well.

8 “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. 9 Six days you shall labor and do all your work, 10 but the seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord your God. In it you shall do no work: you, nor your son, nor your daughter, nor your male servant, nor your female servant, nor your cattle, nor your stranger who is within your gates. 11 For in six days the Lord made the heavens and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and hallowed it. – Exodus 20:8-11 NKJV

The finishing touch of creation was to rest. Just as the fourth commandment was unlike the custom of any other religious society at the time, this designated weekly pause is unlike anything else in our modern lives. Most days, we are bombarded with advertisements for things to do or places to go to “discover” rest or calm or whatever other qualities we want to mark our lives. We have any number of decisions to make in a day about expanding our influence over things. We make plans to increase our own reserves and tend to our resources. We agonize over decisions about where to spend and where to save, whether that is money, energy, or something else. The Sabbath, however, stands outside those concerns. It is not marked by visiting a place nor by obtaining any thing.

This is because our key resource is actually time. Time is the unique resource we can not create more of. One can grow more crops or animals, one can create more gilded vessels, but no one can create an extra day. This is one reason the Sabbath makes no sense from a productivity standpoint. The productivity perspective would be to maximize all the time available to you; “time is money.” What is the one resource you only have a finite amount of, which can never increase no matter how successful or powerful one becomes? Time. – therefore, it is time which the Sabbath commands.

“It is impossible for man to shirk the problem of time. The more we think the more we realize: we cannot conquer time through space. We can only master time in time.” – Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Sabbath

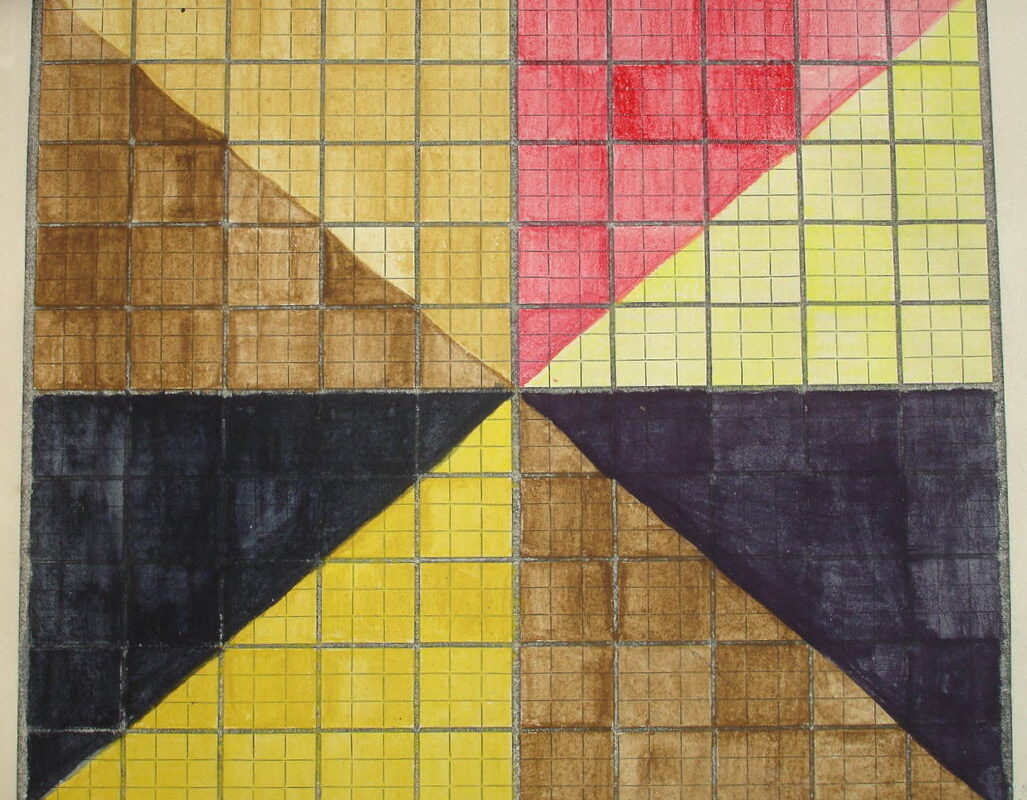

What we do with time determines our experience of that time. When we are distracted, time flies. When we reach a point of concentrated, but effortless work, called “flow,” time passes likewise in a blur, like getting lost in making a sketch or painting, for example. When we are dreading something or bored, time seems to stand still. When we take a trip somewhere new, the novelty of that time, place, and our activities allows us to experience time in a different way, making time seems to expand. This is why a week on vacation spent doing activities you enjoy can feel twice as long as the time it actually lasts. When we take the extra steps to mark a particular moment, that point in time stands out like a beacon, like graduation or wedding celebration. Moments like these feel timeless because of the thought and care put into them. When we strive all week to obtain and manage Things, having one day to refrain from that striving becomes an enjoyable reprieve, a time of refreshment and ease. The Jewish tradition observes the Sabbath from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday. The Christian tradition observes the day of rest on Sunday. However, one does not need to be a part of either tradition to understand and reap the benefits of a weekly day of rest.

How I take a break from tech

In her book, The Sabbath World, Judith Shulevitz details how her family observed the Sabbath when she was growing up. Observing Jews have their grocery shopping done the day before and prepare a meal. They may light candles, set a freshly pressed tablecloth in the dining room, heat the kettle, and refrain from driving. They might invite friends or extended family over to gather around the table for dinner. They set out whatever books or leisure they plan to partake in, do laundry, and clean their living spaces, all in preparation for observing the Sabbath each week.

Clearly, there are dozens of preparations, small and large, to make before observing a traditional Sabbath. What might preparing for a “digital sabbath” entail? Where does this leave us with regards to creating Heschel’s “sanctuary in time”? The most critical aspect, perhaps, is the setting aside and protecting of that time; the “building,” of that 24-hour period. In other words, the most important part about the time, is actually blocking that time to actually observe a “digital” or “tech Sabbath”. Secondly, if our smartphones and auto-play on streaming platforms is “frictionless”, one way to bring more thought to our uses and experiences with technology is to allow them to have more friction. One might respond to whatever messages are outstanding before they you make yourself unavailable for the day. One might chose a movie to watch, or set out a book to read, perhaps even have hiking or biking gear ready to go for the day. You could set up for a creative hobby, like painting, or charge your camera batteries for a long day of photography. The possibilities are endless, really.

For the past six months I’ve experimented with bringing more of this analog friction to my Sundays by keeping them mostly digital-free. I had already spent the past two years not checking social media on the weekends. That alone made a huge difference in the amount of time I had over the weekend, as I had truly free time once again. This experiment, therefore, was not about social media platforms at all. My rules for Sundays are to use devices as little as possible. I don’t check email. I don’t get on YouTube. I often don’t get on the computer at all. If I want to listen to music, I play a CD. If I want to watch a movie, I’ll play a DVD. I don’t ‘ban’ streaming a movie or series, but I treat it as though it were a DVD, choosing something to watch and sitting down to watch it. I don’t binge series or bounce around from service to service. I pick something to watch, enjoy it, then move on with the day. While I don’t get on social media, I do use my phone to call and catch up with family. My aim with these Sundays is not to accumulate arbitrary rules, but to eliminate that which threatens to steal time. In my experience, this has been autoplay settings, scrolling, and the Internet playground in general. On these days, I typically spend a lot of time reading, listening to music, and working on a hobby. If the weather is nice, I make it a point to go outside. The day unfolds effortlessly.

What I have learned

I have learned a few things experimenting with this “digital detox” over the past few months. First, analog continues to prove itself more reliable than wireless. My print books have never crashed in the middle of reading nor refused to open. DVDs, while fragile, don’t become inaccessible due to licensing agreements. I continue to find analog less irritating that its digital counterparts. Secondly, switching contexts with printed material doesn’t seem to weigh down the mind in the same way reading digital material does. I have not yet seen data for this, but my own experience has been that I can read a chapter in a novel, switch to an essay on a completely different topic, then go to a magazine article on a third topic and never feel the brain fog I get after less than two hours of reading online. Even when I read analog for a longer period of time, because it is all on print, the brain seems more receptive and less taxed. I suspect it has something to do with the physical experience of paper; perhaps the spatial awareness and recruitment of multiple parts of the brain reduces the load on any single part in a way digital cannot replicate, allowing the paper experience to be sustained for longer periods.

I have also noticed how time seems to slow down when the day is completely analog. Haven’t we all experienced logging onto the computer to do “one thing,” gotten distracted, and looked up later only to realize two, three, or five hours have passed without our noticing? As entrancing as print books can be, I have never been fully mesmerized by printed material to the degree the Internet often performs, where you sit still for hours staring at a screen. Instead, when I read physical media, I have to get up and move periodically. I notice things around me. I maintain an ability to think, rather than being overwhelmed by a digital Wonkaland. Finally, and most significantly to my mind, I don’t feel as though the day slipped through my fingers, over before it even began. Instead, I’m usually surprised by how much more time stretches before me. In other words, I notice time passing while doing things I consider worthwhile.

Technology can improve our lives, of course, but as with any substance, too much of it can lead to problems. Our task, as intelligent beings, is to find the right balance between using technology in a way which improves our lives and those that diminish our lives. What makes my life feel larger and richer? What makes my life feel smaller and insignificant? Intriguingly, taking out some of the convenience may just unlock a deeper appreciation of time.

Image credit: Pages from Elizabeth Peabody’s Universal History: Arranged to Illustrate Bem’s Charts of Chronology. 1859. Source.