As technology continues advancing, it’s common to hear people say, “I’m no Luddite,” when they make an observation about our increased dependence on technological devices. The term “Luddite” is often used today to describe people who express “anti-technology” opinions. Yesterday’s concerns about factories have become today’s worries over the implications of smart-phones and artificial intelligence, and the term will only continue to gain relevance. But who were these Luddites and what did they want?

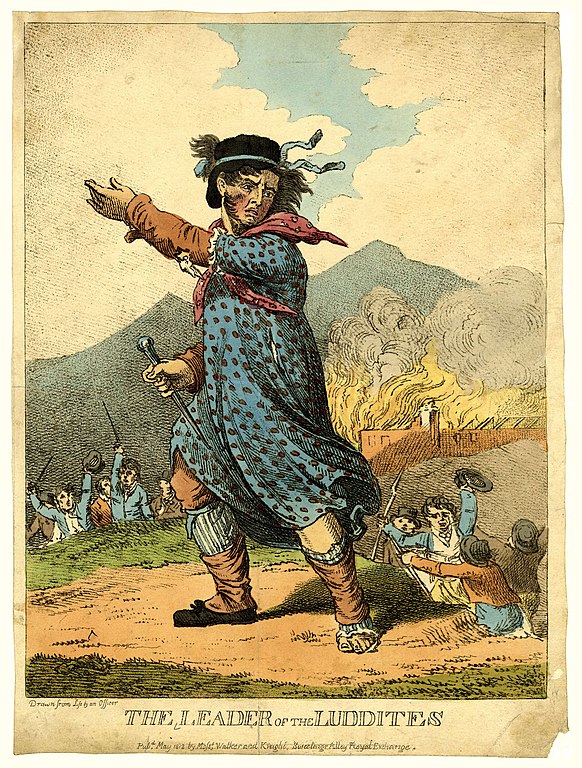

The Luddites were British textile laborers in the early 1800s who opposed the implementation of machines and other practices used to drive down wages or cause unemployment. They took their name from a mythical character the workers united themselves around called General, or sometimes King, Ludd. He was supposedly a former textile apprentice who had been whipped as a boy, and was now exacting his revenge by destroying machinery in textile workshops. Some historians have pointed to the possibility of a worker named Ned Ludd having an episode of some sort and striking his machine (there is debate as to whether this was a purposeful action or accident). There is no consensus Ludd actually existed; like Robin Hood he was said to reside in Sherwood Forest!

The first Luddite riot took place in 1811 in Nottingham, when a group of men broke into a textile workshop at night and destroyed the weaving machines, then fled. These machinery-destroying raids occurred in Yorkshire, the midlands, and the Northwest, – where the lace and hosiery trades were centered – and continued for two years, garnering public support along the way. Tensions ran incredibly high, and some Luddite bands even exchanged gunfire with guards and set fire to mills.

What motivated these workers to rise up against their countrymen and government like this? In the first decade of the 1800s, several factors came together to squeeze British workers. The ongoing Napoleonic Wars continued to devastate the economy; the dawn of the Industrial Age brought machines and factories which could produce exponentially more textile weaving in less time than human hands could work; and, in a particularly tough turn of events for hosiery workers, men’s fashion shifted away from stockings to pants. The textile industry was squeezed, and machines promised higher profit margins for owners. As one author noted, “Hit by the economic downturn, merchants cut costs by employing lower-paid, untrained workers to operate machines as the textile industry moved out of individual homes and into mills where hours were longer and conditions more dangerous.”

In their writings, the Luddites invoked the revolts in France and encouraged their countrymen to join them in rejecting replacement by machine. In Britain, however, the nobility took these uprisings seriously – and took decisive action. By May 1812, over 14,400 troops had been sent to the midlands to quell the destruction. While frame-breaking had previously been punishable by “transportation” to Australia, lawmakers acted to put down this movement quickly. The riots had continued around England nearly every evening since the 1811 Nottingham riot, but they stopped in early 1813, when Parliament passed the Frame-Breaking Act, which made destroying factory machines a capital offense.

The Luddites found support among the English Romantic writers, especially. Percy Blythe Shelley and William Wordsworth wrote poetry extolling the merits of their actions. Charlotte Bronte’s novel Shirley was set during the Yorkshire Luddite riots, shedding light on the perspectives of both the workers and the mill owners. Lord Byron even defended the Luddites in a speech before the House of Lords, highlighting the hypocrisy of those who condemned their actions while profiting from their work. He also published a satirical poem in the The Morning Chronicle days before Parliament voted. The most famous, biting stanza of, “An Ode to the Framers of the Frame Bill,” reads,

“Men are more easily made than machinery –

Stockings fetch better prices than lives –

Gibbets on Sherwood will heighten the scenery,

Showing how Commerce, how liberty thrives!”

Despite their perception today, the Luddites were not “anti-technology” for the sake of merely opposing change. These were skilled workers who increasingly found themselves making less money or out of work entirely. They did not reject technology or machines outright; they were trying to save their jobs! In fact, they used the technology of the time to spread the word about their cause, circulating pamphlets and placing print in newspapers to try to gain support (or make threats in General Ludd’s name). While, the term is often used lightly or dismissively today, the Luddites represented a labor movement, not a band of eccentrics. It’s important to remember these people weren’t simply the 19th-century equivalent of vinyl enthusiasts; they were seeing their industry and lifelong, skill-based careers literally sold off to unskilled workers operating machines, rendering their skills and labor obsolete.

Looking at the the concerns raised today around A.I. and other ways computers render human labor moot (or distort human interactions entirely), I see a modern-day iteration of this Luddite sentiment, which is entirely reasonable, considering people’s livelihoods are in the balance. In light of the violence committed by Luddites, calling strikes to ensure humans continue to be employed to do creative work seems entirely justified. While the term is often used disparagingly today, the Luddites were fighting to continue working. Maybe more of us are Luddites, after all.

Image: Engraving of Ned Ludd, Leader of the Luddites, 1812. (Public Domain)