Some stories are meant to be revisited in certain seasons. While there is an abundance of Christmas literature, I also enjoy having autumnal reads to pick up as the year winds down. Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” is a ghost story worthy of many returns. The delicious language throughout sparks my imagination every time; the descriptions of the farms and foliage as Ichabod winds his way to the Van Tassel farm; the squirrels and birds in their woodland elements; the delectable banquet Ichabod surveys upon his arrival for the evening’s entertainment. It’s all vividly described and incredibly cozy. This is one of the main reasons I enjoy revisiting the story year after year, like a welcome return to comfy accommodations. It feels autumnal from the first paragraph. Then, you encounter the spooky and Gothic elements coming along, with the reasoning behind the name “Sleepy Hollow,” to the ghost stories, to the great build-up and final encounter with that dark legend, the Headless Horseman himself.

In writing my annual Sleepy Hollow post for this year, I was curious about how this story fits into the wider literary history. To what degree could it be described as Gothic fiction? How does Irving’s story compare to fairy tales or folktales? What are the characteristics of all these genres and how do they relate to our frightened schoolmaster, Ichabod Crane? Today’s essay will be an exploration of how these different influences culminate in what is often considered the first American ghost story.

For those unfamiliar with the story, Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” appears in a collection called The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, published in 1820. Set in early nineteenth-century New York, our story takes place in a cozy corner of the Hudson Valley, renowned for its thick forests and famous as a strategic position during the American Revolutionary War. Our protagonist is Ichabod Crane, the dramatically thin, occult-curious schoolmaster from Connecticut, who, earning the ire one of the town’s brawny sons, has his eye on the daughter of a rich Dutch farmer. One night after too many ghost stories and a rejection by this Dutch daughter, Crane finds himself walking through these storied woods, coming to the very stretch said to be frequented by one particularly frightening wayward spirit, the Headless Horseman! Action and antics abound.

What characterizes Gothic fiction?

Gothic fiction, while today synonymous with dark arts, supernatural creatures, and spooky settings, hasn’t always been about the occult or vampires. The first Gothic novel, The Castle of Ortrano, was published by English author Horace Walpole in 1764, with a plot involving a family prophecy, a ghost with ‘an armored hand’, and set inside the titular castle. Walpole’s preface frames the story as an Italian account written in 1529, and recovered during the Crusades. Walpole was inspired, in part, by a nightmare he had had in his home, a Gothic revival structure modeled to look like a castle, later called Strawberry Hill. In blending a real world setting with fantastic elements, Walpole created a new style of literary fiction. The plot is punctuated with instances of portraits which begin to move, secret doors, haunted passageways, and hidden identities, establishing these thrilling hallmarks of the genre from the very beginning. When the novel turned out to be a smashing success – and Walpole was lauded as an ‘excellent translator’ – Walpole clarified the story was entirely a work of fiction. From the second edition forward, The Castle of Ortrano carried the subtitle, “A Gothic Fiction”.

Years later, in 1818, Mary Shelley published her famous Frankenstein, which itself dealt with the limits of human intervention, the macabre, and, supernatural phenomena. Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights has become a sort of poster-child for “Gothic novels,” and it’s easy to see why. It is set in a sort of secluded, large country house, which has its own creepy history. The misty moors which the foreboding house overlooks, along with the stormy countenance of the primary characters themselves, all evokes a terrible feeling of dread hanging over the story. The story itself is a sort of reverse romance, ultimately realized only in death.

However, the name perhaps most synonymous with the development of Gothic literature is Edgar Allen Poe. Poe’s works have astonished and delighted for nearly two centuries, and often draw on themes of death, decay, and entrancement. Poe’s most famous poems, “The Raven” (1845) and “Annabelle Lee”(1850), both touch on the otherworldly elements we’ve mentioned – supernatural beings, doomed romance, and terrorized thoughts. His short story, “The Tell-Tale Heart” (1843) is a particularly vivid example, dealing with decay and guilt, as well as mania. It is unsettling in its subject matter, yes, but even more upsetting is how perfectly calmly the narrating murderer explains his decisions. It shows an unwavering look at and deep understanding of dark thoughts, even madness, exemplifying the Gothic sensibility.

Another of Poe’s works, his short detective story“Murders in the Rue Morgue” from 1841, is such a remarkable example of Gothic fiction, it deserves a short analysis here. First, there are the grisly mystery murders to solve. Investigating brutal murders with no apparent explanation or leads effects a bleak setting. Second, the murders take place in a secluded, sparsely furnished house in Paris, described as “a time-eaten and grotesque mansion.” Third, the Gothic hallmark of “terrifying thoughts”also applies to characters in the story, with their mute astonishments and shuddering without knowing why. More abstractedly, Poe’s detective, Mr. Dupin, himself embodies the qualities of decay by virtue of his family’s declining wealth and prestige. Nothing in the story is bright or hopeful. It brings to mind terrifying thoughts – who could have possibly committed the physical and gory feats described? The revealed culprit (whom you can discover for yourself) strikes a strange tone because it sort of feigns to be supernatural, while still being rooted in our real, physical world. This introduction of something “else” into a setting otherwise much like our own makes the story a particularly Gothic and therefore, unsettling, one.

Ultimately, Gothic stories are often convoluted, many times incorporating tales within tales, switching narrators, and using framing devices such as discovered manuscripts or interpolated histories. Gothic fiction centers on stories where a supernatural or dark element is involved in or impressed upon the story. The story is set in a realistic world, where people react as a real person might, and draws on sensations of fear, terror, and darkness. Other characteristics include sleep-like or deathlike states, live burials, remote locations, unnatural echoes or silences, dreams, the discovery of obscure family ties, unintelligible writings, and nocturnal landscapes.

Sleepy Hollow as Gothic Fiction

Now that we’ve looked at several examples of Gothic fiction, we turn now to examine how Irving’s “Legend” exemplifies the genre. Irving’s “Legend” does line up closely with the Gothic genre, as it possesses a degree of supernatural and dark influence. By immediately establishing an overarching theme of “sleepiness” over the valley, Irving invites a weighing down the senses of the village inhabitants and makes them more susceptible to believe in supernatural causes and ghostly apparitions. Irving gives great attention to describing this portion of the Hudson Valley as ‘tranquil’, and a home of ‘twilight superstitions’.

From the opening passage:

“A drowsy, dreamy influence seems to hang over the land and to pervade the very atmosphere. Some say that the place was bewitched by a High German doctor during the early days of the settlement; others, that an old Indian chief, the prophet or wizard of his tribe, held his powwows there before the country was discovered by Master Hendrick Hudson. Certain it is, the place still continues under the sway of some witching power that holds a spell over the minds of the good people, causing them to walk in a continual reverie. They are given to all kinds of marvellous beliefs, are subject to trances and visions, and frequently see strange sights and hear music and voices in the air.”

Then, by invoking the name of Major Andre, Irving reminds the reader of a dark episode and death, further establishing a scene of grim decay. Major John Andre was a British intelligence officer tasked with handling Benedict Arnold’s treasonous surrender of the crucial fort at West Point during the Revolutionary War. In late September of 1780, Andre was discovered behind enemy lines and hanged for espionage days later in October, lending another element of darkness to Irving’s autumnal story.

While Irving’s legend is blended from historical and various European folktale traditions, he doesn’t incorporate any overtly mythical beings or supernatural imagery one might expect in Gothic fiction. The story is explicitly set in the very real Hudson Valley, near the real village of Tarry Town (today Tarrytown) and plays on the spookiness of ghost stories. Throughout the text, we have descriptions of the valley as ‘drowsy,’ and ‘laconic’, maintaining the ghostly atmosphere. Of course, all of this shadowy allusion builds up to the climactic scene with Ichabod’s terrifying encounter with the imposing Headless Horseman, exemplifying the best of Gothic horror.

Fairy tales and Folktales

After my deep dive into Gothic fiction and some of Irving’s folklore influences, I began to wonder what distinguishes a folktale from a fairy tale? Fairy tales – not unlike Gothic stories, interestingly enough – do often involve supernatural or fantastic creatures; think Goldi-locks’ three anthropomorphic bears, the talking wolf in “Little Red Riding Hood”, the title character in “The Little Mermaid”, and the communication with woodland creatures in the Snow White stories. As you might imagine, the line between folktales and fairy tales is a bit blurry, especially because fairy tales are often derived from much older folktales. Fairy tales are typically (though not always) set in a dream or fantasy world, and usually have happy endings. A fairy does not actually have to be present for the story to be a fairy tale, and likewise, the presence of a fairy does not necessarily make a story a fairy tale. Also, a fairy tale does not contain any moral lessons or instructions. This element does pair nicely with “Sleepy Hollow,” as there is not a moral quality to the story, just pure entertainment.

How do we know when a story is a fairy tale? Marina Warner, in her Fairy Tale edition of Oxford’s Very Short Introduction series, outlines six characteristics of these stories. First, a fairy tale is a short narrative, no longer including novel-length fiction. It possesses a feeling of being old, and is derived from folktales (which themselves are very old). Thirdly, fairy tales contain recombinations of familiar characters and plots; a child making her way through the woods to Grandmother’s house, a prince taking on a dangerous quest to save the princess, children getting lost on their way home. Although there are endless variations upon these simple plots, we can easily identify them as fairy tales, and you can likely name a famous example of each. Fourth, these stories are one-dimensional in that they don’t contain allegory or symbolism to convey deeper meanings. The story is told purely for entertainment’s sake. Fifth, these stories incorporate a sense of wonder and the supernatural. Finally, these stories end on a hopeful note, as with the famous, “happily ever after” final line.

Out of all my reading for this essay, what surprised me most was how recent the fairy tale genre is – only taking off in the 1800s. The founding of the genre is generally attributed to the Grimm Brothers releasing their first collection of stories in 1812. This places Gothic fiction as older than the fairy tale genre, which I did not expect. Fairy tales have always struck me as being very old and passed down from antiquity, but looking into their history, we can see that isn’t the case.

Even more surprising than the fairy tale’s recent arrival is the motivations for story-telling in this way. These fantastical stories involving strange peoples living “long, long ago,” were a source of national pride during the intellectual and moral upheaval caused by the Enlightenment. Characterized by reason and methodical thinking, Enlightenment thinkers prized rationality as the highest ideal in all human affairs, including literature. As thinkers and leaders throughout Europe and North America rejected classical myths and religion, peoples and nations were left without a unifying history or motivation to bring them together as a nation. For many nations – among them France, Ireland, England, and America – that unifying spirit would be found in literature, in creating fantastical myths and glorious peoples from whom the nation could derive a rich cultural inheritance. To that point, Irving’s short story also serves a similar purpose for Americans. We don’t claim Ichabod Crane as an ancestor or anything so literal, of course, but there is a great deal of pride and yearly celebration in this well-known ghost story being an American story, as well as in the fact it was the story to earn America some literary credibility.

As we’ve seen Gothic fiction introduces supernatural, often dark elements into an otherwise normal setting, and follows the reactions of the unsuspecting characters as they attempt to negotiate the strange situation before them. Irving’s “Sleepy Hollow” has the added comedic element of a perfectly reasonable explanation for the ghostly encounter, which only makes it more entertaining, and a story look forward to when the days grow shorter and chillier each autumn.

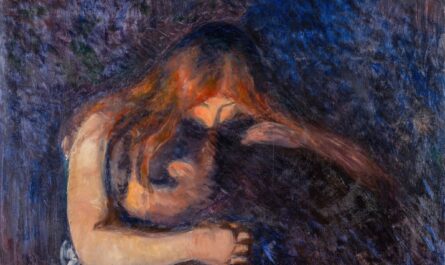

Image: Ichabod Flying from the Headless Horseman by John Quidor, 1828.

Licensed under public domain via WIKIMEDIA COMMONS.