This is fairly obvious, but I love reading.

What may be less obvious is why I love reading, which is what I’ll attempt to articulate. I find it magical, the way reading allows the reader to “download” the ideas of another person into their own mind, and try them on for size. My purpose for reading, whether literature or philosophy or non-fiction is always to sharpen my own mind. “How much of what I think is a result of the time and place I was born into?” “How might my ‘common sense’ thinking be different if I lived elsewhere?” Reading helps answer those sorts of questions.

Reading presents an opportunity to entertain a new perspective. “How might my thinking be more accurate?” “What if this were true?” Books are rife with such opportunities to step outside of oneself and test ideas. Books remain the least aggressive way of engaging with an idea you think you may disagree with, or don’t have any deep information about. By “least aggressive” I don’t mean “easy”. I mean much “less confrontational than arguing with a live person and escalating the conversation away from a learning standpoint”. If you want to learn, you can’t do much better than a book length treatment of a particular conversation or problem.

My list of favorite books read last year illustrates this. One new favorite on that list was Barry Lopez’s Of Wolves and Men, published in 1978. I should clarify that I’m not particularly enthusiastic or invested in news about wolves, or any animal; what excites me about this book is how it was put together. Lopez combines wildlife biology with folklore; interviews Native Peoples around the world who have lived alongside the wolf for generations; he looks at publications and personal diaries from the Wild West of the American frontier, where the wolf was demonized as a ruiner of ranchers’ fortunes. He compares literature written across centuries, and shows how often such “information” turns out to be humans projecting their own ideas onto the wolf. On the surface, it’s a book about the ways in which we really don’t know much about this creature, but on a deeper level it’s about methodically questioning what you think you know and why you think you know it. Lopez implicitly asks you to evaluate your own understanding of facts, even of “common sense”. They aren’t posed directly, but they are simmering beneath the surface, exposed through Lopez’s methods.

My love of reading started very young, being raised in a bookish family in a house lined with bookshelves. I was the precocious child who smuggled books into bed to read after everyone was asleep, only to be caught, have them taken away, and told to go to sleep. Trust, there was another book hidden! When we were little, my father would read the classics to my siblings and me before bed. I cut my teeth on the adventures of Huck Finn and Jim Hawkins, experienced Victorian Paris and London through the eyes of the working class. I was fortunate enough to slip in and out of literary universes as quickly as I pleased, as well as to grow up thinking everybody had a similar experience.

In middle school, I discovered the writings of Francis Bacon and Blaise Pascal, whose prescient observations about the physical and metaphysical world sparked my lifelong interest in philosophy. A few years later, I moved on to Plato and Aristotle, Descartes and Kant, and eventually the successive line of Western thought. It was around this time it dawned on me not everyone reads classics in their spare time. Yet, I still found that surprising. Here were volumes upon volumes detailing the very thoughts of some of humanity’s greatest minds, freely available to anyone who wanted to study, glean, and learn. The majority of human civilization’s successes and failures, documented in books freely available to download and read by anyone with an Internet connection; a fact that still blows me away every time I think about it. What a wealth of information, readily accessible!

This study of ideas, and philosophy in particular, have fascinated me for decades. The aim of philosophy – and in my opinion, the beauty of the discipline – is laying down one’s thoughts in clear language, proceeding from one point to the next to present a clear portrait of what appears to be true. It requires a massive amount of thought and discipline to do so, massive amounts of focus, revising and rethinking, solving any problems arising upon revision, and so on. Once it’s written down, though, anyone may examine it and say, “Oh no, this is where you’ve gone off the mark. Here is what appears to be more accurate.” It’s a centuries-long, worldwide conversation about Truth, open and available to anyone interested and willing to literally do the reading. I love the fact I can sharpen my own mind by sparring with these brilliant minds. I love philosophy because it focuses my own perceptions of reality, and forces me to think more clearly.

That love of observation and sharp thinking probably explains my enthusiasm for another favorite from last year, Susan Sontag’s On Photography, in which she applies sophisticated lines of philosophic inquiry to photography, and what the art form tells us about a society so enraptured by technology. Have we become a voyeuristic society? No one likes that term, of course, but it’s difficult to deny the central place photography (of any skill level) occupies in industrialized nations. As Sontag writes, taking a photograph is both a form of art and a method of control, depending entirely on the mindset and position of the person holding the camera. How much of a factor is possession? Upon arriving at tourist destinations, the first thing one notices is the ocean of cameras or smartphones all pointed in the direction of a famous house, or statue, or picturesque view. We can’t all live in such locales, but we can all carry and possess a pieces of it with us in the form of a photograph. Why does this appeal to so many of us?

While I mostly read non-fiction, one of my favorite fiction reads from last year was Jane Austen’s Emma. Reading this novel was an instance of what Montaigne called “honest amusement;” simply enjoying spending time in the tranquil English countryside of the early 19th century. All the talk of walking through the countryside, lounging around the fireside, or enjoying afternoon tea was cozy, impossible not to appreciate as the days I read it grew colder and shorter. One of the most pleasant parts of reading fiction -whether it be Victorian literature, an H.G. Wells novel, or an adventure story running through a jungle – is being transported to a radically different time and place, breathing in the air of a foreign land and walking around in a new atmosphere.

And so, it is the experience of this new atmosphere – whether it’s found in non-fiction titles, a philosophical text, or classical literature – and bringing those questions back the realm of daily life, which makes reading, for me, such a thrilling experience.

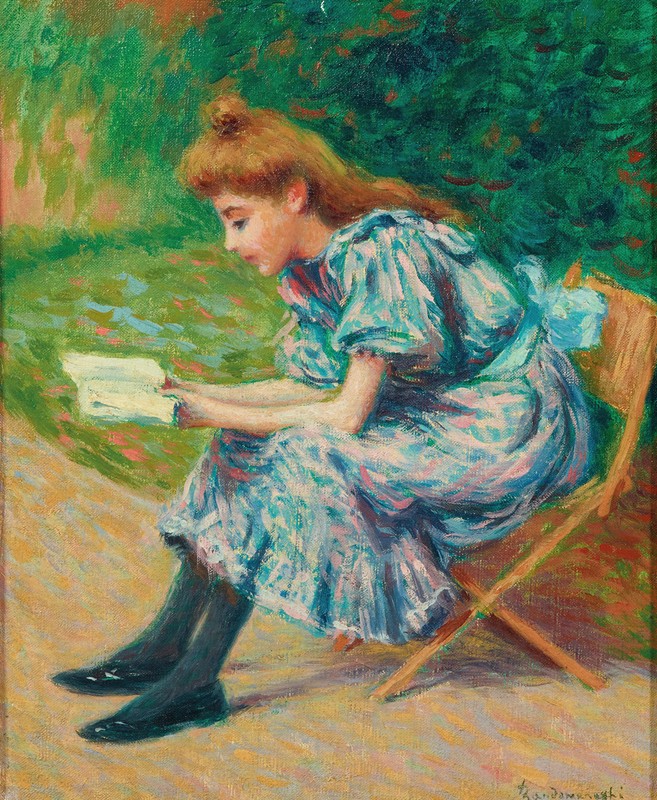

Image: “Reading Young Lady” (La Liseuse). Federico Zandomeneghi (Italian, 1841 – 1917)