Every Friday I round up the most fascinating breakthroughs and concepts from the realms of history, psychology, the arts, and literature; and post them in my ongoing series, Five for Friday. In no particular order, here are the best ideas I’ve come across in the first half of this year.

If you enjoy this round up, you might also enjoy my monthly newsletter, where I break down the books I read each month, and outline ideas like these.

One:

“I notice that when all a man’s information is confined to the field in which he is working, the work is never as good as it ought to be. A man has to get a perspective, and he can get it from books or from people — preferably from both. This thing of sleeping and eating with your business can easily be overdone; it is all well enough—usually necessary—in times of trouble but as a steady diet it does not make for good business; a man ought now and then to get far enough away to have a look at himself and his affairs.”

— Harvey S. Firestone (written in 1926)

*

Two: “We worry because we care.”

Novelist George Saunders with some non-traditional thoughts on writers, worry, and trusting the process.

*

Three: We are living in an era where the language of feeling outweighs the language of fact.

From the abstract: “After the year 1850, the use of sentiment-laden words in Google Books declined systematically, while the use of words associated with fact-based argumentation rose steadily. This pattern reversed in the 1980s, and this change accelerated around 2007, when across languages, the frequency of fact-related words dropped while emotion-laden language surged, a trend paralleled by a shift from collectivistic to individualistic language.”

*

Four: This has become my go-to reminder for revisiting books:

“Now, there is a law written in the darkest of the Books of Life, and it is this: If you look at a thing nine hundred and ninety-nine times, you are perfectly safe; if you look at it the thousandth time, you are in frightful danger of seeing it for the first time.” – G.K. Chesterton

*

Five: In Praise of Memorization

“Knowledge is at our fingertips and we can look anything up, but it’s knowing what knowledge is available and how to integrate it into our existing knowledge base that’s important.” – Pearl Leff

For my own part, even memorizing less “useful” knowledge, like poetry or quotes from school, has resulted in those ideas and references becoming reflexes. “Death be not Proud,” I memorized in junior high, and it still comes back to my conscious mind when the topics of death or perspective arises, challenging me to look at a topic from various viewpoints.

*

Six: Bruno Cucinelli, the luxury sweater maker with the soul of a philosopher: “Let’s try looking after our soul while working. Do you know that we work 11 percent of our life? We can’t have everything revolve around work.”

*

Seven

This piece can be read two ways: the first is a literal interpretation of the “not grand” beauty of the Texas landscape, with which I fully relate. The second is as an allegory for adopting perspectives; an alternative way of looking at an issue may not be immediately obvious, but looking elsewhere and back with an altered view might just help you discover why someone else finds it so great.

from Austin Kleon

*

Eight: “The deep life cannot be reduced to concrete steps. But without concrete steps, you’ll never get closer to it.”

This is true of most deep things, I think.

*

Nine:

I can’t believe it took me this long to discover this amazing quote, which summarizes one of my core beliefs! “Accept the truth from whatever source it comes.” – Moses Maimonides. What matters most is not the source, but whether the content of their claim is verified as true or not.

*

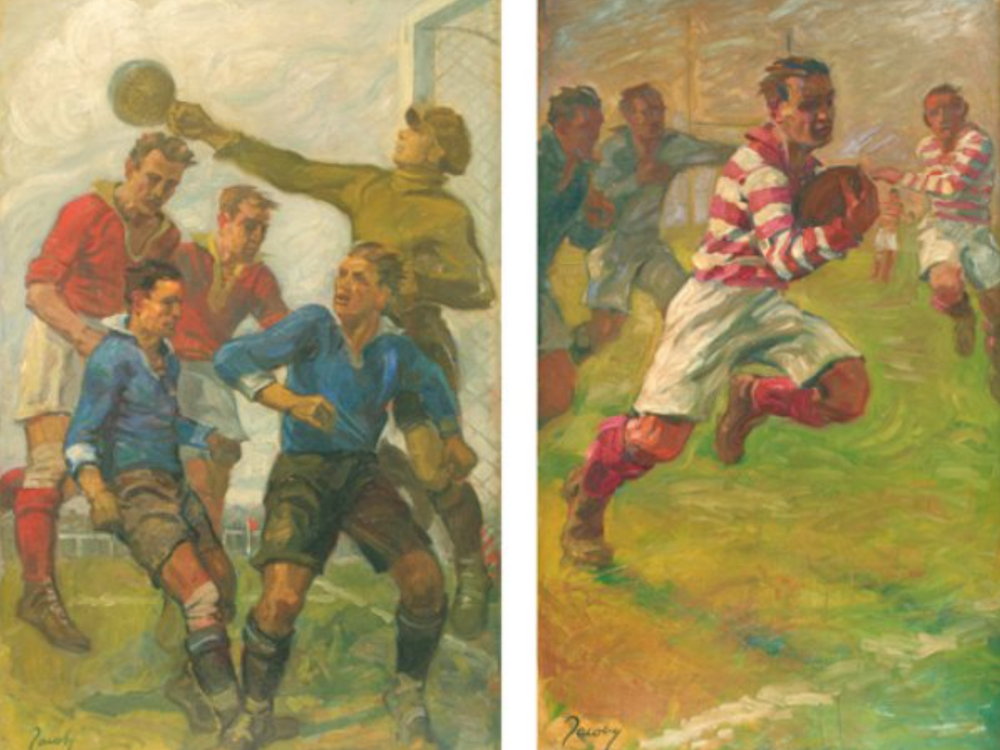

Ten: The Summer Olympics used to include an arts competition!

From 1912 to 1948, painters captured the action and were awarded medals according to five categories: architecture, painting, literature, music, and sculpture. Each had to capture the spirit of competition and had to be original.

Here are two examples:

*

Eleven: “Everything that needs to be said has already been said. But since no one was listening, everything must be said again.” — André Gide

Hence the continued need for writers and journalists.

*

Twelve: One of my favorite essays of this year, Nomen est Omen, explores the purposes names serve and looks at the many ways a name influences a person and vice versa. It’s surprising and delightful reading.

*

Thirteen: This counter-intuitive working idea from James Clear has made such a difference in the quality of my drafts, and the overall time and quality of my output. By setting an upper limit on the amount of time I will work in a day, suddenly the pressure is on to create well and quickly. It has been a game changer over the past few months of very limited time to write.

*

Fourteen: “Surprising detail is a near universal property of getting up close and personal with reality.”

Even things which appear simple are composed of several, component tasks all brought together to work as a whole. For example, going for a walk involves putting on shoes, grabbing your housekeys, locking the door, choosing a direction, navigating traffic, winding your way towards your destination, remaining on the sidewalk, maintaining the correct direction, then doing the same on the return trip. That’s just for taking a simple walk by yourself! Building and creating new projects are exponentially more complex. Imagine the complexity of building a multi-story house or an interstate highway!

*

Fifteen: A resonate passage from Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s 1978 Harvard Commencement Address,

“We are now paying for the mistakes which were not properly appraised at the beginning of the journey. On the way from the Renaissance to our days we have enriched our experience, but we have lost the concept of a Supreme Complete Entity which used to restrain our passions and our irresponsibility. We have placed too much hope in politics and social reforms, only to find out that we were being deprived of our most precious possession: our spiritual life.”

*

Sixteen: “There is a trend in logo design that started around 2017-2018. It’s as if many companies decided that being unique was a handicap and that it was better to be like everyone else.” Why would companies decide it was better for a logo -typically meant to stand apart – to blend in with every other company logo?

*

Seventeen: Erik Hoel’s theory that we stopped making geniuses because we stopped aristocratic tutoring seems plausible to me, and at the least must be a factor in U.S. education outcomes today.

*

Eighteen: How does one find something worth saying?

Justin Murphy offers two good solutions for finding something to say: (1) “classical erudition, old-fashioned and patient study of great works, and (2) adventure + introspection. Do literally anything hard, risky, or strange, and combine it with thinking.”

via David Perell’s Monday Musings newsletter.

*

Nineteen: Earlier this year, I came to the conclusion that television is entertainment, inherently and only valuable in the context of amusement. Thinking, and especially thinking well on serious topics, happens away from television. At best, shows and films can prompt you to learn more about a fascinating event, person, or idea, but it can’t explain that topic fully. It certainly can’t foster discussions of that topic, as the only rule of the medium is to not be “boring”. Only the individual mind, with effort and concentration, can do these things. This idea comes from Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death, which has completely shifted my perspective around film, television, and the expectations we can have of the medium.

*

Twenty: The question – “How can parents respond to silly questions from their children without stunting their creativity or inquisitive spirits?”

Mortimer Adler’s response includes advice applicable to us all. The most compelling is, “They [parents] should be able to tell a hard question from a silly one, and not treat everything that perplexes them as foolish.”

“Not treat everything that perplexes them as foolish,” is a great goal for any and all adults engaged in discourse. Not understanding something doesn’t inherently reflect upon that something’s veracity. certainly, more people could first, reduce the number of things that perplex them by choosing learning, rather than entertainment, and secondly, cultivating a sense of wonder and curiosity.

*

Twenty-one: “But the Builders do not repair. They build. That’s because building is virtuous. Unlike, in their mind, criticism, which is passive and vampiric in nature, building is active and generative. It is a de facto good to build, regardless, perhaps, of the outcome.”

Building is good. Maintaining objects and systems of worth is also good. We can’t get into the trap of thinking we will always build something “better.” Sometimes the better route is simply repairing what is already there. “For what purpose?” is a powerful question to ask before setting out to build. Know the problem you want to solve.

*

Twenty-two: An interesting reframing of a popular idea. “No one is smart enough to be wrong about everything.” – Ken Wilber

via Mark Manson.

*

Twenty-three: “If one day one grasps that their busyness is pathetic, their occupations frozen and disconnected from life, why then not continue to see like a child, see it as strange, see it out of the depth of one’s own world, the vastness of one’s own solitude, which is, in itself, work and status and vocation?” – Ranier Maria Rilke, from Letters to a Young Poet

*

Twenty-four: “Just about every Western book written before World War II assumed Christian knowledge. Familiarity with the Bible is, therefore, a prerequisite for reading any piece of classic literature. How are you supposed to understand Dostoevsky or Paradise Lost if you’re not familiar with the Bible?“

A compelling line from David Perell on Why Everyone (especially those who consider themselves intellectual) Should Read the Bible.

*

Twenty-five: Charles Dickens’ defense of Sunday as a leisure day for all, not just the elite who live in leisure. “Sunday Under Three Heads”, written in 1836, is a response to a proposed (and defeated) bill which would have effectively allowed those who could afford to employ servants to enjoy their labor, but not allow those who would patronize ale houses or purchase a meal from a restaurant to do so on Sundays.

While Europe respects the Sunday “sabbath,” (whether they practice a religion or not) as a guaranteed weekly day free from labor, the U.S. has moved away from this vital hallmark. This single failure signifies a total disregard in the States for the work-rest balance required to produce quality results from people, and has predictably resulted in a society all but devoid of rest, respect, dignity, and compassion for the human being.

If you’d like to receive ideas like this, sign up for my monthly newsletter.

Photo: Photo by Brandon Morgan on Unsplash