“Put more thought into your leisure time.”

– Arnold Bennett

Focus and leisure are not opposites. In fact, leisure requires focus. We often make the mistake of thinking about leisure as a default for time not otherwise spoken for. “Leisure time” is a sort of inevitable label for time not working. However, this betrays a misunderstanding of this pivotal concept. The Greek word for leisure is scole, from which we derive our word “school,” and indeed leisurely topics like philosophy, literature, and rhetoric formed the basis of education for centuries. Similarly, the Latin term for leisure is otium, which refers to a specific time put aside to engage with the divine, as philosopher Josef Pieper describes. This specific time could be used to explore art or music, be spent contemplating philosophy, or refer to time in spent in meditation.

True leisure is focused and deals with concepts greater than any individual; it’s meant to restore the soul. Leisure and focus are not opposites, but in fact fuel one another. The best work flows from a mind immersed in leisure and leisure itself requires focus.

Deep Work

The ability to focus is and will become a defining factor in the world of work. In Deep Work, Cal Newport observes how the world of work has shifted from physical labor to knowledge work, hinging on the ability to produce high quality work quickly. Those who are able to work efficiently in this new economy will be those who master the art of deep work. To do so, one must control their time and be able to focus on work for extended periods of time. At the same time deep work is increasingly vital, new technologies diminish our focus and make it more difficult to focus our attention longer than a few minutes. Emails, social media notifications, messaging platforms, in addition to wi-fi connected devices, make it more challenging than ever to hold one’s attention on a single task. To navigate this digital minefield, one must develop a system prioritizing focus.

Newport argues we should aim to default our days toward focus, not distraction, and, that by placing boundaries on time, we can protect our focus. We protect focus by eliminating the potential for distractions. The most effective way to do this is scheduling time for deep work, as well as down time, to give our brain a rest. Newport recommends knowledge workers build their schedule to prioritize hours of deep work when you’re at your best, letting the shallow, less cognitively demanding tasks make up the peripherals of the day. This allows us to have the best of both worlds; quiet, dedicated time to mull over and solve problems, without pushing into “fried” territory. Deep work is about preserving focus and time for everything that’s important to you, not solely work tasks.

The entire philosophy behind Newport’s system can be summed up in a single word: focus. We’ve seen focus is clearly vital during working hours to accomplish everything in a shortened window of deep focus. What may be less obvious is how vital focus is in leisure.

Pieper on Leisure

Leisure does, in fact, require concentration. It is not a break from focus. In his essential essay, Leisure, the Basis of Culture, philosopher Josef Pieper examines the origins of leisure, tracing its definitions and components from ancient Greece and contrasting this definition with the modern (mis)understandings of the concept. This treatise is a foundational piece of twentieth-century philosophy and required reading on the topic. Pieper’s definition is three-fold. He begins by establishing leisure to be an attitude of inward calm, of being “not busy.” Secondly, he describes leisure to be a sort of contemplative celebration. “It is not the same as non-activity,” he writes, “nor is it identical with tranquility; it is not even the same as inward tranquility.” Because the historical basis for leisure comes from the festival, as Pieper shows, leisure is a celebration of those ideals which make each of us more human.

Thirdly and arguably most importantly, leisure is not a mere function of work life. It stands opposed, he says, to the ideas of work as a social function. “A break in one’s work, whether of an hour, a day, or a week, is still part of the world of work. It is a link in the chain of utilitarian functions. The pause is made for the sake of work, and in order to work, and a man is not only refreshed from work, but for work. Leisure is an altogether different matter…” Leisure then exists for its own purpose, and is an inward, celebratory calm contemplation of the divine. It is more than mere free time – it’s time set aside with a clear purpose.

That purpose is celebrating and becoming more human, not more efficient at your job. Leisure is about more than simply recovering from work, more than simply not working. It is about bringing dignity to the human soul. This is why true leisure is spent building up the most human aspects of ourselves; investigating philosophical truths or enjoying timeless music or reflecting on art. It is communing with our higher selves, with the divine. The concept of vegging out or spending time doing nothing, while valid and necessary, isn’t actually leisure. This is relaxing or even recovery time. Leisure is an act of contemplation, an active function of the mind working, but not straining. It’s not simply a break from, but a moment of pursuit.

On the Rise of Scheduling Free Time

As calls become more common for more time for family and leisure and fewer hours at the office, a number of people who seem unable to take satisfactory breaks has emerged, too. They claim their efforts to make space for free time have left them even more stressed out and in some cases, working longer hours. Let’s examine why their free time may not be truly restful and restorative.

“To combat the inevitability of busyness, people are increasingly scheduling in their free time – reserving it in their calendars the way you would a doctor’s appointment or a lunch date. …But, while many find scheduling free time a liberating godsend, others find that it simply becomes yet another stress-inducing practice.

“Many people I spoke to felt forced to schedule free time after severe mental-health problems, panic attacks, anxiety and depression; unable to guarantee the mental space to wind-down, scheduling in free time was the only work around. But even if they believed that scheduling free time was, in some cases, a lifesaver, people also felt frustrated that their lives had demanded such radical action. “It kind of depresses me”, “I shouldn’t have to schedule free time”, and “it feels weird having to set boundaries on my time” were common responses to adopting this method.”

-From The New Statesman

These statements reveal a misunderstanding of purpose. The intention behind scheduling free time is to create time and space to recover from work. The only way scheduling free time will work is by first limiting your working hours. This is why Newport recommended boundaries for work hours. Free time won’t just appear; it has to be taken from other areas. Limiting work hours creates margin for everything else.

Why limit work hours? Parkinson’s Law dictates work expands to fill the time allowed – a project will take up as much time as you give it. You’ve likely observed this in your own life when you had a report due at work or school. For example, let’s say this report is due in three weeks. Three weeks – that’s an eternity! If you’re like I was in school, you’d imagine working on it bit by bit, slowly bringing forth a superb project by refining it over multiple passes over those three weeks. Of course, something else would get done instead, and I’d end up completing the entire project in a flurry of activity, working down to the last minute. I had three weeks to do the report, but got it done in the final two days.

Imagine what could have happened had I approached it with that same frantic energy from the beginning. Instead of doing it in two days from the beginning, I allowed it to occupy my mental agenda and take up much more time than it actually needed. It expanded to fill three weeks, when I clearly was able to finish it in much less time. My point isn’t to do work as quickly as possible. The point is that by procrastinating, I wasted thirteen perfectly usable days, when the project only actually required two days. We do the same thing in our professional lives, allowing smaller, less demanding projects to take up much more time than they should.

The solution is to focus and give yourself less time to do the work. By employing focus, we enable ourselves to get our work done in less time. Then, we enjoy the scheduled time off. This is the principle behind Deep Work as well as seventh week sabbaticals. You work hard to get everything done during those reduced hours, then enjoy having space and time with no obligation in your blocked off free time. Because each block has a focus, there is a clear separation between work and rest. We are not trying squeezing more activity into an already over-packed schedule; we are carving out time and assigning it a purpose. It’s a subtle but critical distinction.

The folks interviewed are approaching this problem from the opposite direction, trying to fit “free time” into an already full schedule. Understandably, they’re frustrated by the results. Instead, we start from purpose; creating dedicated time to work without interruption. When that time is up, focus on those things which you enjoy and fulfill you.

Other Objections

The other major objections in the New Republic piece were “I shouldn’t have to schedule free time”, and “It feels weird having to set boundaries on my time.” I’ll address both here in turn. First, why would we not schedule free time? We schedule the things which are important to us – birthday parties, phone calls, soccer practice – to make sure they happen. If you don’t schedule free time, the odds are you won’t have any free time. Blocking off time in your calendar to specifically not think about work is about ensuring that separation actually occurs. Setting boundaries on your time is taking responsibility for how you spend each day. It’s a proactive method of making your time work for you.

Perhaps a change in perspective can be introduced here. Free time is not about putting activities on the schedule so much as prioritizing the activities which make you more human. Putting “relax” down for a half hour in the afternoon, as one interviewee did, simply does not work. It is unhelpful because it only ends up stressing you out more when, inevitably, something disrupts that time. We also don’t relax on command, and the middle of the workday is the worst time to attempt to do so. Further, this person is trying to fit more into a day, without first taking out the slack, as we’ve discussed.

The second objection is similarly flawed. Of course it’s going to feel “weird” setting boundaries, when the concept is new. Any new habit starts out feeling tedious and awkward until you adjusted to the change. That doesn’t mean it’s not a worthwhile endeavor. The short-term and minor disruption of putting limits on your work hours pays off over the short- and long-term. In the short-term, you have a few more hours of rest. Over the long-term, you’re able to work harder on projects you enjoy, you’re able to think more clearly because you have the mental space to do so, and you’re less stressed because you aren’t taking on more work than your schedule can accommodate. The minor inconvenience of placing limits on your time is worth the long-term clarity and reduction of stress over months and years. Setting boundaries on time is how we “find time” to accomplish our goals. Further, as Pieper illustrated, time for leisure is necessary for the health and wholeness of our higher selves.

It’s easy to see how focus and work relate to one another; you must focus to complete your work efficiently. The connection between focus and leisure is less obvious, but leisure does require focusing your attention. Focus and leisure go hand in hand because they both deal with attention. The difference is where you focus your attention; leisure focuses on those timeless pursuits which feed your soul. Transcendence demands mental attention and energy. What pursuits can you enjoy simply for their own sake? Consider things like art, classical music, reading philosophy or great literature; things which exist of and for themselves. Leisure is the exploration of whatever makes you more human. Perhaps it’s as simple as sitting back and watching nature carry on around you.

Leisure is a narrowly defined concept, dealing with the nourishing of the human soul and demanding attention for those things which exist in their own right. Far from a dismissal of attention, leisure is a channel for focus. By thinking about these foundational concepts correctly and making time for true leisure, we can bring our work and leisure selves into less conflict with one another.

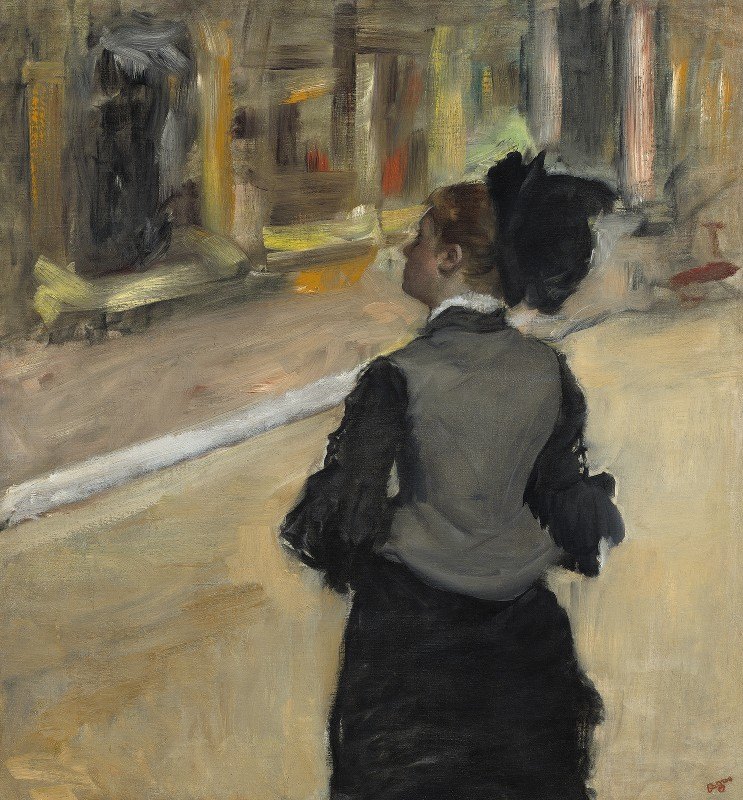

Photo: Woman Viewed from Behind (Visit to a Museum) (c. 1879-1885) by Edgar Degas