What is an epitome? Today, the term ‘epitome’ denotes the most condensed version of a piece of writing or a topic. It turns out, epitomes were actual written summaries of texts popular during the middle ages. Those epitomes were similar to today’s abridgments. While epitomes were summaries written by others, abridgments are only composed of quotes from the author’s original work. Epitomes became popular for studying because they were smaller and therefore cheaper to produce than the original works of many authors. Their ubiquity allowed more people than ever to read and caused literacy rates to skyrocket. For the first time in human history, a sort of “canon” encompassing cultural literacy was possible through the summarization of texts into epitomes. Today’s epitomes are typically called “companions,” like the Oxford Companion to the Iliad or Oxford’s Companion to the Brontë’s.

The long history of epitomes is a fascinating reminder that humans have been summarizing and condensing knowledge for as long as we’ve been able to circulate thought in print.

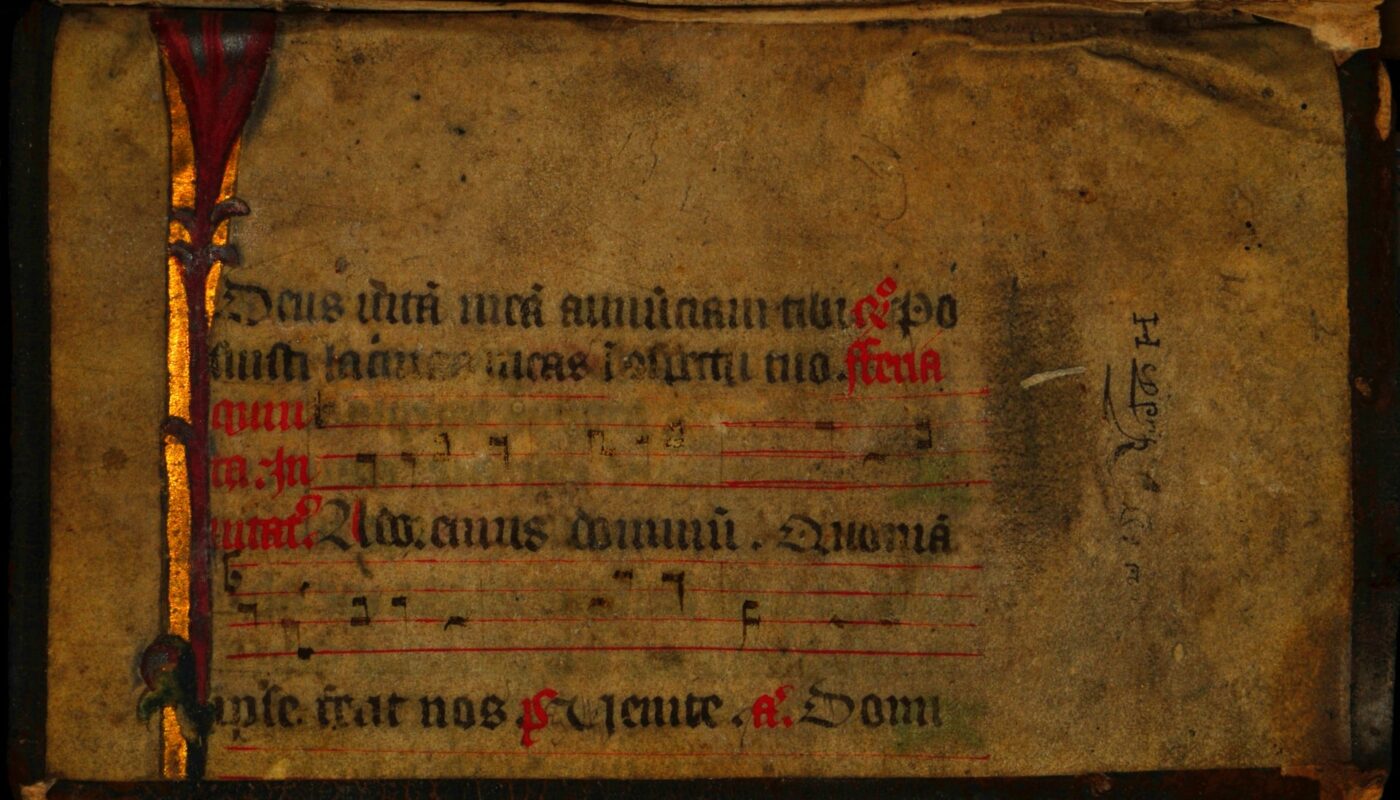

El Libro de Los Epítome

The most famous epitome must be the recently discovered Libro de Los Epítomes, a sixteenth-century text compiled from a library containing thousands of books and unseen for over 300 years. This epitome was written by Christopher Columbus’ son, Hernando Colón (also Ferdinand Columbus), who was convinced Spain would rule the world. Therefore, Colón thought, the Spanish should have an organized catalog of all written human knowledge. Just as Columbus was burdened with glorious purpose to conquer the physical world, his son was similarly impressed to conquer the world’s written texts. Colón wanted to gather every book in the world, refine its wisdom into a summary, and categorize the knowledge so a single person could learn from and use the system. Colón considered his library a “brain,” housing all the knowledge he could find across the world so any question could be answered, and all the world’s information was preserved.

This massive collection was built from 1509 until his death in 1539, and was compiled during his travels throughout Europe. As Colón bought books, he noted the locations and prices he paid for them, along with the exchange rates, and often included his thoughts on the book. He wasn’t only interested in classic texts, either. Colón bought and recorded local periodicals, popular texts, and even weather reports to maintain an accurate representation of the popular literature and information characterizing the time.

Scholars compare Colón’s library to an early iteration of Wikipedia or Google – an attempt to gather, organize, and access the entire world’s knowledge. Colón’s epitome was one of four catalogs of his library, containing an index organized by keyword; an index of the authors listed in alphabetical order; an index of topics covered; and the epitome, which summarized every title in the impressive library. The library itself contained 15,000 books, only 4,000 of which remain housed in Seville today. Each of these books were read, summarized, and logged. Then, the entire collection lay dormant for over 300 years.

Colon’s extensive cataloging process was the key to the epitome’s discovery. “It’s great to have it all, but it’s pointless if you can’t find your way around it,” Guy Lazure, a historian at the University of Windsor, said. “That’s one of the great things about his thoroughness, and how meticulous he was. He annotated all his books the same way.” Lazure discovered the epitome, though he didn’t immediately realize what a monumental find it was. “I didn’t know it was THE missing catalogue,” Lazure said. “I had found the only surviving copy.” The epitome, one of two originals, contains references to books and research which no longer exist anywhere else, making it a critical addition to historians’ understanding of 16th-century Europe.

The epitome was discovered in 2018 in a library collection at the University of Copenhagen. The collection was created way back in 1730, when Icelandic professor Árni Magnússon donated his collection of nearly 3000 manuscripts and printed books to the University of Copenhagen, where he worked as a history professor. How did a Spanish manuscript end up in the private collection of an Icelandic historian? It’s believed he bought it in a collection of Icelandic manuscripts, and this one simply was overlooked and left sitting on a shelf for generations. Currently, the epitome is being digitized and translated, to be made available to the public.

The discovery of the Libro de Los Epítomes gives insight into how educated learners read hundreds of years ago. As this “book of summaries” reveals, reading and summarizing information is how we continue to use and benefit from the things we read, long after we turn the final page. Whether using a commonplace book, or another method of indexing, keeping track of all your accumulated wisdom in one “brain,” is a great way to not only find information, but to refresh your understanding of it.