Isn’t the news vital to democracy? Aren’t we citizens obligated to be informed about our government and current events so we can make good decisions at the polls? Isn’t the news the best way to be informed?

In a pre-internet world, perhaps. Now that every person on the street has unfettered access to the internet, and can instantly post their hot take to be shared millions of times, no. Over the last forty years, the priorities and practices around news media shifted from information to “info-tainment.’ The news has gone from being scarce, authoritative, and factual, to a 24-hour quest to entertain the masses. It’s no longer enough to watching the evening news religiously; we must insist on high quality information and guard our attention more carefully than ever.

The definition of being informed

It is important to know basic facts about our government, leadership, and the policies or bills being proposed. Outright ignorance is not the answer, and not my argument. However, today’s news fails to provide high quality and meaningful information, which is why we should stop watching it. Being informed is knowing about topics of national interest, their context in history, and being aware of the ideas about the best ways to approach those issues going forward. The purpose for being informed is to put yourself in a position to make thoughtful and prudent decisions in elections or to help people in crisis; it’s to be a responsible and involved citizen. It’s to understand the direction the country is moving and how that affects you and your loved ones. It’s part of a bigger picture, and it doesn’t stop at knowing the headlines. Knowing headlines but having no context to understand them is the antithesis of being informed.

From the nation’s founding, the press was established as the public forum to hold the government accountable. This is remains the primary and most vital function of the news, as free speech hinges on the freedom of the press. However, this sacred function is seldom employed. Most published stories are not Watergate or the Pentagon Papers. Instead, we get daily “updates” on stories which haven’t meaningfully changed in weeks. We get press releases trumpeted as though they actually represent a consequence or policy change. Most concerning, instead of holding the government accountable, we see members of the press pandering in coverage of their preferred politicians.

Gresham’s Law and Today’s “News”

A generation ago, news was restricted to two channels, keeping it scarce, factual, and focused. Over the last forty years, news has shifted from appearing balanced and attempting to convey fact to the lowest common denominator of melodramatic opinions and salacious headlines. Compare a broadcast of the CBS Evening News from 1971 to any recent prime-time cable news segment. You’ll wonder how such different formats were produced by the same organizations only a generation apart.

A quarter of a 1971 episode of the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite addressed developments in Vietnam and the conditions leading up to the decision to pull troops out of Laos. There were statements from government officials played over film shot on the ground in Vietnam three days prior. Then, remaining on the topic of Vietnam, Cronkite touched on American POWs receiving letters and businessman John Fairfax’s efforts to free these POWs. There was no commentary, no “experts” brought in to pontificate on the issues. In a later segment on Boeing’s unemployment prospects, a few workers were asked their opinions on the manufacturer’s developments and future prospects; each clip was twenty seconds and included both the question and answer in their entirety. This stands in stark contrast to today’s prime time news programs, where the major news channels traffic in three second clips, circus antics, and punchlines, instead of factual updates.

While the internet hastened the shift from print to digital, the smart-phone accelerated the evolution of notifications, likes, and “breaking news alerts,” and created the attention economy. This has increased competition and resulted in reporters publishing dozens of articles every day, not because there is so much to report, but because these companies have to direct massive amounts of traffic to their websites. The pressure to have fresh headlines at all hours, combined with the need to attract viewers and beat out the competition on a developing story means fact-checking and validating sources are abandoned in favor of “breaking news” coverage. These stories are often tips from a single source and are rarely validated before being published. These stories are run with disclaimers stating the story and details may change as facts emerge. An infamous example of this was the decision by CNN and the Washington Post to run the ‘Covington teens’ story in late January 2019. The media jumped the gun, writing inflammatory headlines for a story, which was based entirely on a seconds-long clip of a tense exchange after the March for Life in Washington, D.C. Hours later, when the longer video surfaced, it revealed the inflammatory descriptions of aggressive and racist white teenagers harassing elders to be inaccurate. By that time, all the major news sources had run the story on their websites and social media pages with those inaccurate headlines being viewed millions of times. In the rush to be first, the media completely omitted fact-checking and context, instead writing the most compelling headlines they could come up with to garner clicks and views. The teens sued for hundreds of millions of dollars, and the lawsuit ended in a settlement. This fiasco represents the quality of reporting we can expect from a 24-hour news cycle dependent on the attention economy.

This change can be explained using Gresham’s Law, an economic principle which states “bad money drives out good money.” In our case, low quality reporting drives out higher quality journalism. When all it takes is a smart phone and internet connection to report “news,” an abundance of low quality sources flood the marketplace. These are stories which would never have warranted mention a generation ago, but are now rounding out prime time news reports. With a deluge of low quality information constantly available and always expanding, it comes down to you and I to be selective about the news and information we consume. Instead of accepting sensational headlines and empty reports, we must choose to focus our attention on factual, measure, good sources of information.

The Moral Argument

The most frequent push back to not watching the news I’ve encountered is the citing of a moral duty to be an “informed citizen.” If the description of being informed includes a general knowledge of the country’s leaders, their political party and policy platform, the current social climate, and potential solutions addressing social issues, none of that is dependent on the news. Going a step further, can anyone realistically make the argument that watching the news in its current state has created a more involved, empathetic, and responsive populace or government? On the contrary, watching the news feels like fulfilling an obligation, but doesn’t accomplish much. You feel outraged, you listen to a few short clips (which lack context, but in which people are sure fired up) which spark anger or indignation, then you continue on with life, having checked the box of “being informed.” When was the last time watching the news or knowing the headlines made you change your mind about politics or social causes? That impact simply doesn’t come from the news anymore. If we are truly looking for quality sources to dispense high quality information, which might spark lasting change in society, the news is simply not up to the task.

My argument isn’t that people shouldn’t know the major social issues of the day or who the president is, but that the news is no longer the best source of this information. Going a step further, with the news in its current “info-tainment” state, I contend watching it undermines any potential benefits it may hold, because it tricks you into thinking you’ve accomplished something. No one would accuse reality television of being critical to understanding current social attitudes, yet watching talking heads yell at one another is held up as some sort of moral obligation. Stop watching wrestling, and start wrestling with the issues yourself.

“Won’t I miss the important things?“

Today’s news falls into two broad categories: first, the many emotional headlines which feel important, but have no long term significance; secondly, the real news and substantive changes which take months or more to develop, move so slowly they are difficult to discuss, and don’t make headlines because they are terribly boring. Consider the differences illustrated by Buzzfeed and CSPAN; one writes junk articles short on substance, full of ads, and always linking to something else you should read right now. The other is timely and records changes in public policy, but it moves so slowly most people aren’t interested in watching. Generally, we want to ignore the first category and dive into the second.

Most stories fall into the first category. Pictures of destitution from around the world, or images from explosions in far-flung places feel important, but don’t affect much change. As emotional as such stories are, most are forgotten with days, if not hours. Likewise, much of what gets reported simply is not news. Press releases and daily briefings are not news. Joe Biden eating a corn dog in Iowa is not news. Theorizing about celebrity couples or feuds is not news. These are filler to keep news sources top of mind for when actual news takes place, because, like any commodity, it’s designed to keep you coming back for more.

The second category, which covers genuinely important news, will filter through. I’ve experienced this time and again. For example, since 2013, I haven’t watched cable news, yet I’ve still known about elections, the pandemic, outrageous comments from various politicians, and the deaths of numerous celebrities. In January of this year, when the Capitol was breached, family told me what had happened within hours. When significant events happen, people will tell you. They’ll email or call; they’ll bring it up in conversation. The important news will find you.

Important news also takes time to emerge. It takes time to gather and sort out details. Those hearings on policy and debates over bills before Congress are important, and they contain dozens or hundreds of pages of proposals. They are more complicated than a two sentence blurb or catch-phrase can possibly convey. Even historic events like the Capitol insurrection continue to take months to break down and examine. The earlier example of the Covington story also illustrates how important it is to allow more information to come to light. The world is complex, and it takes time to sort through the details.

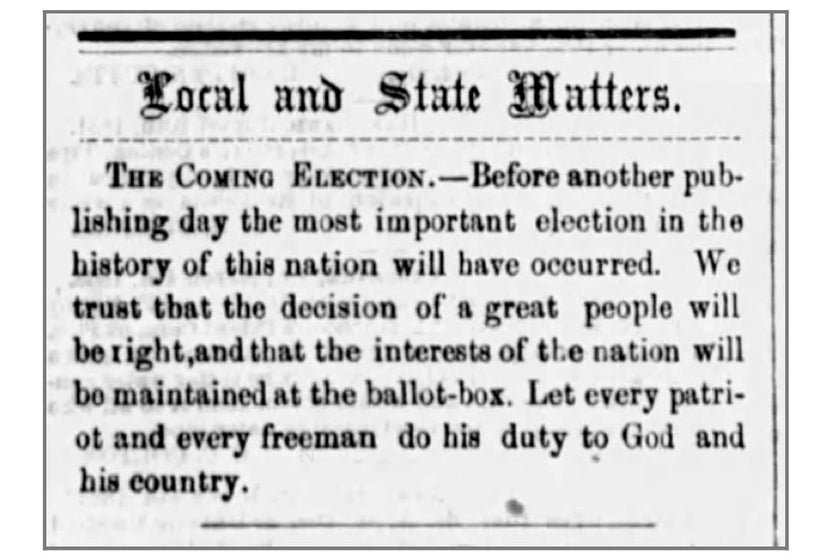

In the eight years since I stopped watching the news, I’ve learned much more about people, culture, and social issues than I would have by watching the evening news. By removing the constant chatter of news updates, I’ve been able to learn about the people and places around me. I’ve changed my mind on social issues after reading multiple perspectives around them. I’ve learned about the culture of the United States throughout history, and about how we’ve been individualist and self-motivated from the beginning. I have context for current discussions around racial tension and immigration. I also don’t get bent out of shape hearing the latest sound-byte from a politician. I just think back over how many ridiculous political statements this country has survived. I don’t get caught up about elections being “the most important election of our lifetime,” a line literally used every four years. Every person I’ve heard from who has traded in their cable news for high quality journalism has reported the same findings, as well.

Being informed is no longer a result of simply watching the news. Being informed means being able to put the events and perspectives of the day in proper context. It’s being able to see how historical choices have led to the current moment; recognizing which paths have already been tried and found wanting. It’s being able to make wise decisions because you understand the conversation taking place. It takes time to understand these things, time to consider a path of action; that’s a lot more time than the news dedicates to any topic. To be informed is to have a long view of history. Being tossed around from headline to headline with each news cycle is to exhibit a lack of understanding about the nation’s history.

How to Stop, and What to Consume Instead

My recommendation is to completely cut out all news sources for a month. Stop watching cable news. Completely remove social media updates. Opt out of notifications from news websites and pages. With this method, you are entirely removed from the constant chatter of updates and junk “news” clogging up your timeline and thoughts. You have time to breathe, think, and experience life without the tyranny of the new. After that month, you can add back in what you actually miss.

If cutting out the news completely seems extreme, reduce the number and frequency of sources you hear from. Instead of subscribing to daily updates or notifications, switch to a monthly or weekly edition of the news source. Harper’s and The Economist are both reasonably neutral sources and offer a free weekly round-up email edition. Subscribe to the Sunday edition of the New York Times or other major papers. A weekly format allows time for the facts to emerge in actual news stories – giving fact-checkers a change to do their jobs – and leaves less room for filler stories. Any time you find yourself cruising the headlines, ask yourself: Is this story going to mean anything in five years? Or even five weeks? If the answer is no, why bother?

How to Inform Yourself

Long-form journalism

Look for high quality outlets publishing long-form journalism and pay for them. Subscriptions to The Economist, Foreign Policy, and Financial Times are pricey because good journalism is an investment. Flying journalists in to discuss policies and events with government and business leaders, access to research papers and institutions, and the fees to secure experts all require a lot of money. By the same token, you don’t need to have a subscription to every outlet, just a few who publish the highest quality journalism. Their work goes through multiple edits and rounds of approval, an intensive fact-checking process, and is reviewed for months before being published. These long-form pieces give context to the issues they discuss, which will deepen your understanding of events and changes and their implications.

When you find a topic that strikes your interest, dive deeply. Read essays and books from people you expect to agree with and those you expect to disagree with. Dive into how the topic was understood historically, how it is understood today, and how it might be improved going forward. Look for how it relates to other areas of society. Work to understand, to be less wrong, and not just to be right.

Read books

Books provide the most high quality information in the least amount of time, giving you the most bang for your buck. Authors spend years researching and tracking down experts to weigh in on their topics. Then, only the best and most convincing arguments are gathered into a volume for you to digest over a few hours. Books are also underrated as sources of perspectives on social issues. Reading older books will expose you to unfamiliar ideas and perspectives. Instead of reading popular titles, look for titles on the same subject from a century ago. Look for how the current issues became the issues as we know them today. You’ll understand the conversation more fully – why this is being discussed, what’s been done before, and how those past views shape what different sides think should be done now.

Go to the source

Learn to read technical reports. This will give you the actual data, and allow you to work towards your own conclusions. Most basic information on equations and statistics is widely available online. Use these resources and learn to read research for yourself. Coverage of new studies often misinterprets the findings; reading these papers yourself will let you read reports without the interpretation from a third party.

The information you’re looking for is on an organization’s website. The news is an outdated conduit of information. It was useful when politicians, leaders, or businesses couldn’t communicate with large groups at one time. That’s no longer the case. All these news sources release their own information, and they all have websites or social media pages you can check if you’re interested. For example, when Congress considers a bill, the actual text of the bill is posted online for anyone to read.

Finally, check your local news websites for updates unique to your area, like weather updates or local elections. The changes which will most directly affect your daily life are those local concerns, and most lasting changes follow persistent efforts at the grassroots level. Don’t underestimate the good that comes as a result of starting small.

The Information Diet

Think of the news, articles, films, and video you consume as a sort of diet – an information diet. Whereas the basic building blocks of food diets are vegetables, protein, and grains, the major building blocks of an information are books, essays, and long-form content. The bulk of your information diet should be a few in-depth pieces of reporting which is considered, written, rewritten, and finally published to meet a high standard.

Then, add in your intermediate pieces. You need a bit of fruit and healthy fat to round out your diet, but it doesn’t take much. This intermediate level is made up of movies, prestige television, fiction novels, most podcasts, and magazine articles. They are fun, yet contain substance.

Finally, your junk food. This is your desserts and candy. Sure, you need a tiny bit to keep you sane, but you’d be foolish to build your diet around this sort of intake. When you only eat sugar, your body is deprived of vital nutrients. When the extent of your research is watching prime time cable news and reading 200-word “articles,” you drastically limit your understanding of the world, its complexities, or how those issues could possibly ever be solved. You give yourself virtually no chance of making an informed decision.

After quitting the news, you’ll notice you don’t find yourself freaking out about the latest gaffe from a politician, or the “updates” and press releases which are heavy on buzzwords but devoid of significance. As you switch your intake to higher quality information sources, you’ll notice you not only don’t need dozens of smaller articles to get a clear picture, but you don’t want them. You’ll be more knowledgeable about the topics which interest or concern you without the stress of emotional and trivial headlines. You will become truly informed.