The tools don’t make the [artist], but the artist should be able to locate her tools when she needs them Note taking is an essential part of reading and retaining what you’ve learned. Taking the note is the easy part, though. The challenge comes in going back and finding that funny quote about humans and houseplants or that great story idea you had last Tuesday. Those notes – like any tool – are only useful if you can locate them when you need them.

How have great academic and professional minds tackled this problem? By creating an index or filing system. Today we’re going to look at past and present writers and the systems they’ve developed so they never have to waste time tracking down a note.

George Carlin’s categories and subcategories

George Carlin was one of the most influential comedians in the world when he died in 2008. Considered the “dean of counterculture comedians,” Carlin recorded fourteen comedy specials for HBO, and appeared in various movies and television programs. Over the course of his nearly fifty year career, he wrote and told thousands of jokes, compiled from millions of notes. To keep this wealth of information organized, he first used an analog, then switched to a digital file system, starting with a main subject title, and sub-divided by topic. Here is how he described his system,

“There’s a large segment of it[his filing system] devoted to language, which is a love of mine. And a rich area for my work talking about how we talk. One of the files is called “The Way We Talk.” And it’s about certain voguish words that come into style and remain there. But then there are subfiles. Everything has subfiles. There’s one that says “Crime.” There’s “Crime” and there’s “Law,” there’s “Sex” and there’s “Race.” And there’s “Humans”—that’s obviously a big folder with a lot of smaller folders in it, it’s about the human race and the human species and experiences and observations I have about that, or data that I’ve found about it. You know, 6 million people stepped on land mines this year. Those things interest me.”

…

“And there’s “America,” and America is a major category, of course. It breaks down into the culture, and the culture breaks down into further things. It’s like nested boxes, like the Russian dolls—it’s just folders within folders within folders. But I know how to navigate it very well, and I’m a Macintosh a guy and so Spotlight helps me a lot. I just get on Spotlight and say, let’s see, if I say “asshole” and “minister,” I then can find what I want find.”

A digital system makes searches simple, obviously benefits from being available virtually anywhere, and only takes up as much space as your computer.

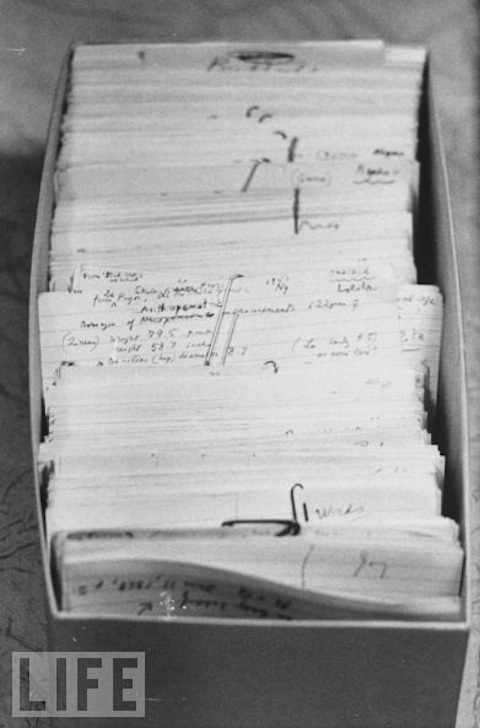

Joan Rivers, Ryan Holiday, and Vladimir Nabokov use an index card method

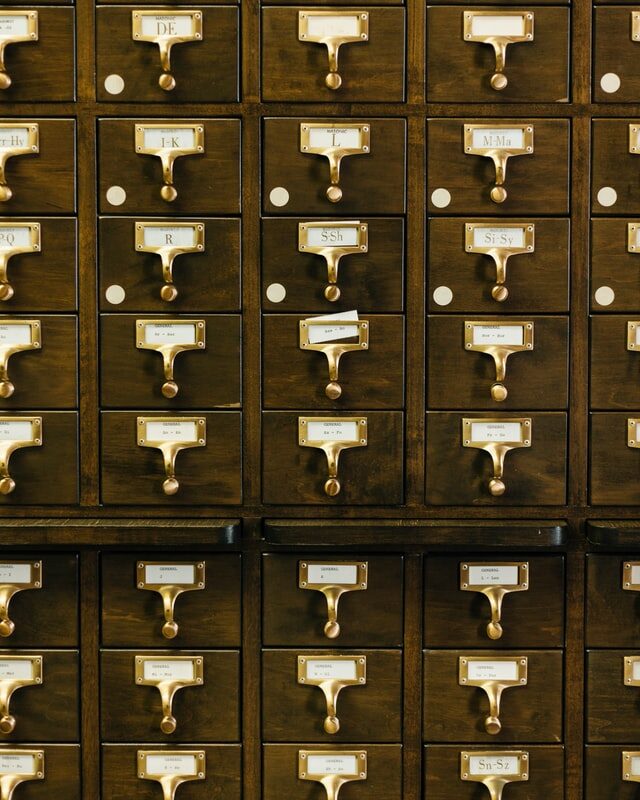

These three writers – though covering different topics in different ways – share a similar process. Each uses index cards, which are then filed according to topic. Comedian Joan Rivers hand wrote down every joke she composed – well over a million – and filed them in a card catalog which stayed in her office in her Upper East Side home. She remarked the most difficult part of the process was deciding which topic to assign to the joke. Author Vladimir Nabokov used 3×5 cards which he filed. On them he wrote memos to himself and discussed the subtle differences in word choices. He also kept blank cards under his pillow should inspiration strike in a dream. Stoic author Ryan Holiday prefers 4×6 cards, and uses them not only for creating manuscripts, but as his commonplace book. Every note, every striking quote from a book, observations from his life and conversations; it all gets taken down on a note card and filed by topic.

The card catalog system allows for easy organization; you can find a complete quote on a dedicated card just as easily as pulling a book off a shelf. The physical act of writing out your notes and observations also helps your mind recall the information more easily. For those who have the space to dedicate to binders, file folders, or card catalogs, this method would be a simple and impressive physical representation of the knowledge you’ve found over the years.

David Sedaris’ detailed, daily notebook and recurrent transfers

David Sedaris is a comedian, radio host, author, and essayist. He takes copious notes to document the happenings and feelings of his day. He writes about the walks he takes, the shirt he wears, his expectations of the interactions he’ll have this afternoon. He then extracts bits and pieces to create a story, to turn our attention to a truth, or to create a scene in his writing. As he told Fast Company, one piece began as “a diary entry from a trip to Amsterdam. He met a college kid who told him he’d learned that the first person to reach the age of 200 had already been born.” From there, Sedaris, “speculated that the first person to reach the age of 200 would be my father. And then I attached it to something else that had been in my diary, that all my dad talks about is me getting a colonoscopy. So I connected the 200-year-old man to my father wanting me to get a colonoscopy, and that became the story.”

His process is taking daily observations down into a notebook. The next morning, he revisits the previous day’s entries and expands those notes into journal entries. He then prints out and binds the entries four times a year. In addition, and arguably most importantly, he creates an index organized by story topic and volume number. No detail is wasted, and the process of revisiting entries sparks creativity and playful combinations, which become his essays, books, and stand up comedy routines.

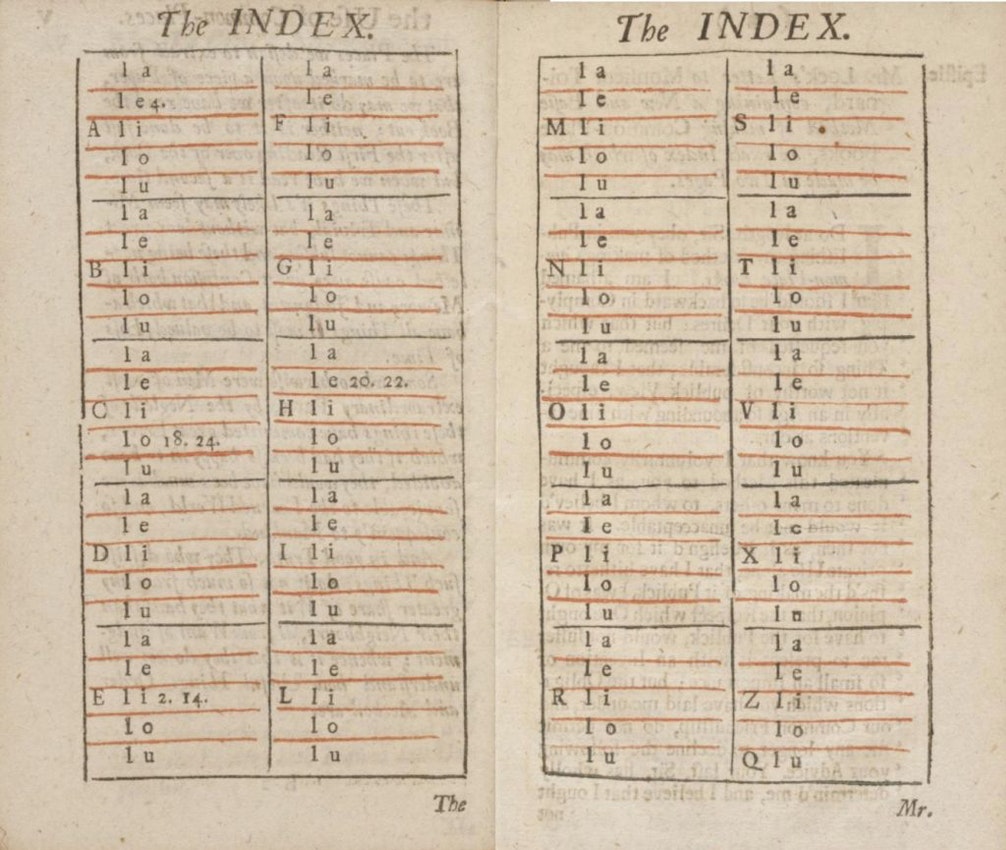

John Locke’s two page index

Physician and philosopher John Locke used an ingenious method for organizing his commonplace book in just two pages. Locke began keeping a commonplace book his first year at Oxford University, and his method for indexing would become common practice for the next one hundred years.

Published in the French Méthode nouvelle de dresser des recueils in 1685 (later translated into 1706’s New Method of Organizing Common Place Books), Locke describes the index like this, “When I meet with any thing, that I think fit to put into my common-place-book, I first find a proper head. Suppose for example that the head be EPISTOLA. I look unto the index for the first letter and the following vowel which in this instance are E. i. If in the space marked E. i. there is any number that directs me to the page designed for words that begin with an E and whose first vowel after the initial letter is I, I must then write under the word Epistola in that page what I have to remark.”

What a novel idea to organize by vowels! It takes up less space, yet still allows for quick location of a topic. This method allowed him to index more topics and ideas on a single page than a more traditional method might. It’s orderly enough for him to find the exact term he is looking for, given the alphabetical order, yet messy enough for dissimilar ideas to mingle and inspire novel ideas. Having created an index of the notes and quotes he accumulates, he can then scan this index to locate a note, or just flip through from idea to idea, seeing what strikes his interest. Really, this sort of alchemy is exactly what most writers and thinkers want and need.

Thoreau’s progressive repetition process

Henry David Thoreau also began to keep a daily journal while in college. Later, this journal grew and evolved to take on more lofty and professional meaning. Thoreau’s approach to journaling is more intentional and stylistic than most of us think of when we think of the word “journal.” His process was to actively take notes while out in the fields, or while studying, then expand those field notes into stylized and edited journal entries. Those thoughtful journal entries were rewritten to become his lectures. Finally, he expanded and refined these lectures into essays, which informed or made up his published books.

This method of repetition is useful for allowing an idea to settle in and germinate. Instead of approaching a topic, then quickly moving on, Thoreau allowed himself the time and space to ruminate on a few key topics, like nature, and develop a distinct and articulate perspective on them.

Thomas Jefferson’s copied and bound letters

In 1823 Thomas Jefferson wrote, “The letters of a person, especially one whose business has been chiefly transacted by letters, form the only full and genuine journal of his life.”

While the founding father only wrote one book, the patterns of Jefferson’s life are indeed illuminated by the thousands of letters he wrote in his lifetime. The topics of these copious letters ranged from diplomatic greetings to scholarly expositions, and the recipients spanned his beloved family and friends to new acquaintances. He corresponded with the leading scientists of the day, keen to understand the latest breakthroughs in biology and naturalism alongside discussions with his fellow lawmakers and diplomats on the most prudent forms of government.

Such a wide range of interests certainly demands organization. Jefferson made a copy of each of his letters, bound them, and filed them alphabetically according to topic as well as chronologically. This would allow him to see the evolution of his own understanding of a given subject, as well as with whom he might discuss that topic further.

David Perell’s digital notes and progressive repetition

Writer David Perell uses a digital notebook to keep track of his notes and ideas, calling the notebook his “second brain.” While the digital format makes finding a particular quote or statistic easy, the best part of Perell’s writing process is his method of note-taking. He, along with a couple select writers, inspired my own method of note-taking and organizing, as follows: When taking notes on a book or essay, quote only the most important and best parts. Write a summary in your own words, and include how or why the information stands out to you. Then, organize these notes according to topic, not source. For example, if you were reading a biography on Thomas Jefferson and taking a note on his letter writing, you would file the note under the topic of writing or correspondence, not under the author of the biography.

The genius of Perell’s method is that it mirrors Thoreau’s many revisions iterations, while also taking advantage of the digital ease of categorizing knowledge. By continuing to revisit the notes you made initially, you add more detail or branches to the core idea, advancing and increasing your understanding of the topic and it’s many applications. Over the following weeks and months, you’ll review this information and connect it to other existing and future notes. The spaced repetition will reinforce the ideas, and prompt you to think about those ideas in new ways, as they connect to increasingly diverse ideas and people.

As always, the best method is the one that works for you. Take inspiration from these great writers, take what works, and tweak the process of creating and locating those notes into something entirely your own.